I’ve been digging in to Thomas Fleischman’s wonderful book, Communist Pigs. It is a history of pig farming in East Germany (GDR) during the Cold War. I’m reading it alongside the also excellent Porkopolis by Alex Blanchette and The Nature of the Future by Emily Pawley. I’ll be reviewing all three of them together for Public Books, so I’ll keep my comments about Communist Pigs relatively brief. Meanwhile, I’m also writing an essay on the poet and social critic Wendell Berry. I’ll use this occasion to flesh out some of my thoughts on Berry, who plays a minor role in Tom’s book.

Fleischman explains how German state-owned farms, emblematized by an enormous pig farm in the Brandenberg town of Eberswalde, borrowed from the US to buy feed from the global grain market, fed that grain to “industrial” pigs, and then exported pork back to the West. Sound familiar? Fleischman’s central claim is that, by the 1980s, pig farming in the GDR was indistinguishable from American-style agribusiness in technical, economic, and environmental terms. Indeed, virtually all of the weaknesses of American agribusiness models were also evident in the GDR, an observation that should chasten, rather than reassure American ag boosters. Fleischman introduces Berry as a placeholder for critics of agribusiness, and, in doing so, references one of my all-time favorite nits to pick:

Fleischman is quoting from Berry’s iconic 1977 polemic against industrial agriculture, The Unsettling of America, and elsewhere in that text Berry specifically attributes the quotation “get big or get out” to Eisenhower’s Secretary of Agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson. Since 1977, countless other books and articles on farming, some even by notable and excellent writers, have reproduced that attribution. For some reason, Michael Pollan muddied the waters in Omnivore’s Dilemma by attributing the quotation to the head of the USDA under Nixon, the oft-villainized Earl Butz. (Berry has plenty of nasty things to say about Butz, but he does pin the line on Benson, not Butz.) Regardless, it is now commonsense in agricultural and environmental writing that Benson (or sometimes Butz) told an audience of farmers directly that they should “get big or get out,” and if you’re interested in pithily summarizing the industry-capture of the USDA, that’s the way to do it.

The problem? I doubt Benson ever said it.

You can’t prove a negative, they say. But, at the very least, I can definitively assert that I have never seen any first-hand evidence that documents the quotation or its context. And I’ve looked far and wide for it! It’s not in any speech or paper of Benson’s I’ve seen. If Benson said it, it went unreported in any newspaper or magazine, and it went unremarked in Congress where Benson was a regular object of scorn. Indeed, it would be just the sort of juicy line that Benson’s most ardent critics would cite (Benson had many, many critics). One of them, the leftist journalist and former-USDA official, Wesley McCune authored a whole book about Benson. It’s packed full of direct quotations from Benson (often tediously so), but you won’t find “get big or get out” among them.

Historian-ing is, at its best, a collaborative effort, so perhaps I just missed the evidence that others saw? I’ve checked the footnotes of the various books attributing the line to Benson. If they cite anything, they cite only other secondary texts that are equally murky about the details of the utterance. I’ve also directly corresponded with a handful of historians who quote Benson and none have been able to produce any actual documentary evidence for the claim. Some agree with me that it is almost certainly an apocryphal quotation, while others are, ahem, quite defensive about it. The closest I’ve come to anything resembling evidence is this 1958 article from the New York Times about how much farmers in Minnesota hated Benson:

In other words, by 1958, Benson’s detractors were summarizing his views as “get big or get out,” which is not the same thing at all as providing evidence that Benson said those particular words.

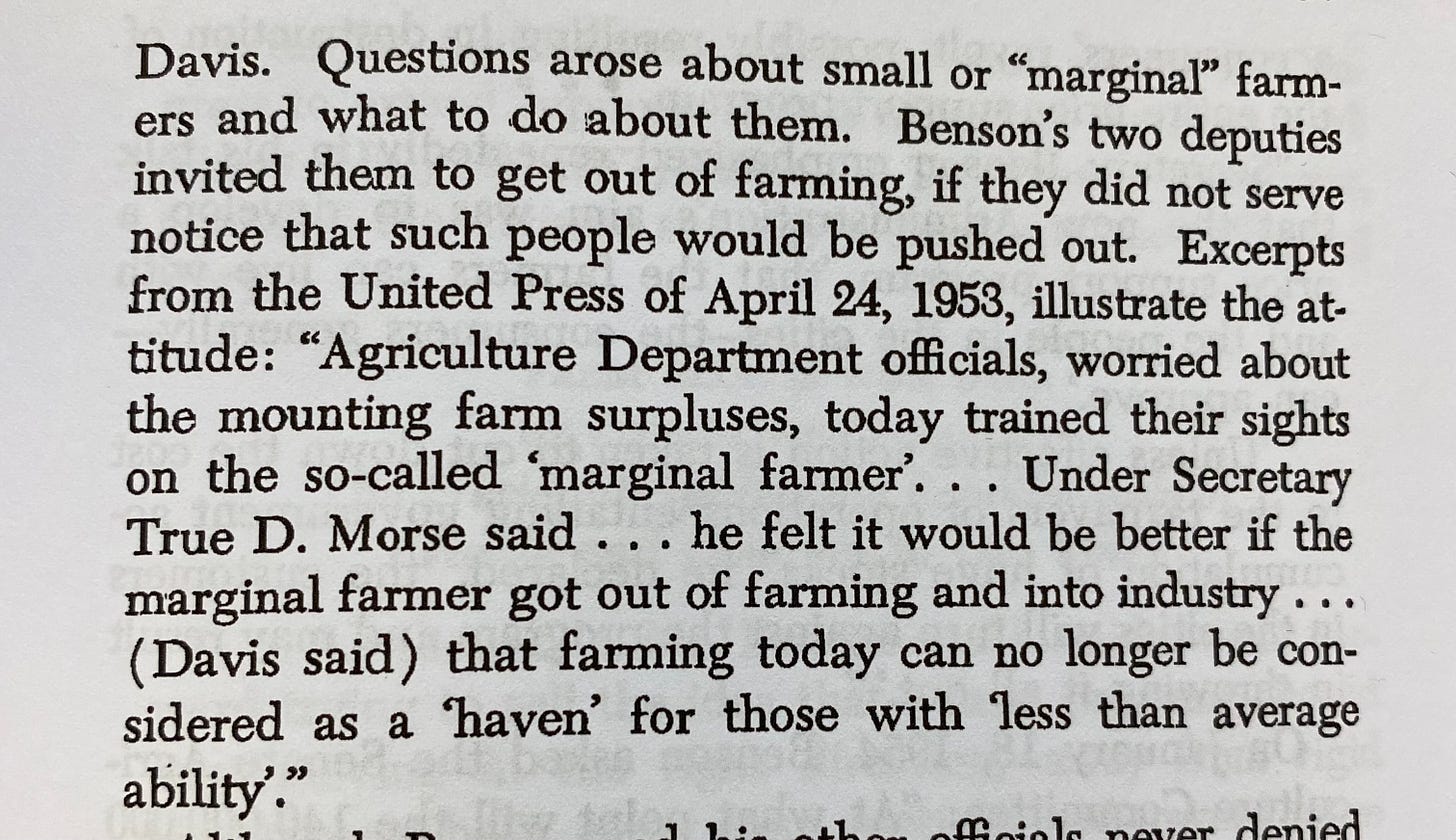

Benson had, by 1958, said a great number of controversial and unpopular things that could be construed as similar to the quotation at issue. For example, Benson’s “General Statement on Agricultural Policy” from 1952 drew ire for the claim that “inefficiency should not be subsidized in agriculture or any segment of our economy.” And, in 1957, Benson stated, “At present there appear to be a few more people in agriculture than are needed.” Similarly, many of Benson’s deputies in the USDA voiced opinions many interpreted as insensitive to the challenges facing small farmers and Benson did little to chasten them or distance himself from their views. McCune summarizes one such incident in terms that edge up to the quotation (“get out of farming”) but still falls short of it:

One could parse whether a “marginal farmer” is necessarily a smaller farmer, but it doesn’t really matter: That’s True D. Morse speaking, not Benson.

Finally, the most thorough study of Benson’s tenure at the USDA by a contemporary historian is Bryan McDonald's Food Power. McDonald has combed Benson’s speeches and letters far more extensively than me (or any other historian I know) and here’s how McDonald presents the quotation:

You’ll notice the words “associated with” and “his supposed advice.” I haven’t discussed this directly with McDonald, but my guess is that he shares my skepticism about the quotation’s veracity and that’s why he refuses to directly attribute it to Benson.

(Meanwhile, some of Benson’s detractors don’t sound all that reasonable to me (from the same article as above):

Ah, to have the moral certainty of a 24-year-old!)

If one accepts that “get big or get out” is apocryphal, you could still argue that it, nevertheless, accurately summarizes Benson’s policies. That is, after all, the substance of the NYT quotation above and the accusation that Benson didn’t care about small farmers was regularly leveled at Benson since he began to push for alterations in the USDA’s subsidy scheme in 1953. At the time, Benson sought to reduce price supports for commodity crops, which had been effectively pegged to pre-World War I levels through the New Deal. Benson’s critics charged that this would be disastrous for smaller, less capitalized farms. That’s a fair charge (though, imho, not bulletproof), but it overlooks Benson’s pivotal role in the legislation, PL480, that created the Food for Peace program in 1954. Through that program, the USDA essentially purchased surplus commodity crops and then dumped them into markets throughout the global South as “international aid.” PL480 was an enormous boon for all commodity farmers in the US—large and small—because it artificially propped up the prices of commodity crops in the US, but it did so at the expense of farmers in those developing markets, who found themselves scrambling to compete with cheap American crops.

That’s not to say—by a long shot!—that midcentury wasn’t a rough stretch for American farmers, but it’s not accurate to say that Benson was indifferent to small farmers. He might have been inept and ideologically rigid, but in terms of his political speech, he regularly expressed moral concern for small farmers. Here’s how McDonald summarizes the situation:

To zoom out, then, I’d like to give a few take-aways about why I think this is interesting and important:

1) It’s a fascinating case-study in historical methods! The number of professional historians quoting Benson saying something he probably didn’t say is much larger than the number of historians expressing public skepticism about it. Tracking how the probably apocryphal quotation got into public memory as a definite fact requires some detective work. My own theory is that although Benson never said it, his detractors, including McCune, used the phrase to summarize his approach. My guess is that Berry (who was a reader of McCune’s) was careless when he wrote Unsettling and the popularity of that text then catapulted the quotation to its current status. Again, how Michael Pollan arrived at Earl Butz is another matter, but also perhaps due to carelessness.

2) On a related note, Berry, although a beautiful and powerful writer, is a polemicist and a sloppy historian. His critique of agribusiness is cogent and incisive because of this—historical detail frequently derails the clean lines polemicists would draw—but many of his readers don’t register this and read Unsettling as an accurate appraisal of American agricultural history. Frankly, many of its claims about agricultural history vary from unfounded to downright absurd. For example, Berry portrays efforts to conserve soil as a legacy of a tradition of small-holding husbandry that was neither scientific nor capitalist in orientation. This is… simply not true! (And then there’s the weird polemic about indoor plumbing…)

3) This brings me to the third and intentionally less finished point: for all his strengths, one of Berry’s signature pernicious legacies has been to treat concepts like scale (“small”) as transparent and ahistorical without theorizing them specifically in relationship to technology and political economy. This, in turn, has tended to produce leftist food writers, imitating Berry, who struggle to deal with scale in a nuanced and intelligent way. Instead, scale—again without historical context—gets locked into the Manichean framing that suits Berry as a polemicist but isn’t economically or ecologically useful: big is bad, small is good. What those terms mean in 2020, 1977, 1900, 1850, and 1750 are quite variable and there is simply no single “small farming” legacy to nominate as Berry does.

Worse still, that mode of thought also results in a deeply reactionary unwillingness to think about a positive role for the state in food systems, as well as a tendency to organize moral concern exclusively around a particular heteronormative kinship structure (“family farms”) that also just so happens to transmit property. From that perspective, white land-owners are objects of moral concern and deference, while brown and black laborers are excluded from both family and property—always treated as peripheral and disposable. This deeper problem—how we define moral concern in the context of farming and how it reinforces reactionary concepts of property, labor, and race—is ultimately what makes it impossible for me to take (early) Berry seriously as a leftist critic.

Well done! Some economic geographers (Dick Walker comes to mind) are fond of challenging this fetishization of scale by saying that there is no difference between small and large farms (under capitalism). Which gets liberals upset pretty quickly, haha, but is also its own kind of polemic...Of course, DW has a much more sophisticated understanding of agricultural dynamics than this, but it seems that is the rhetorical strategy he finds most useful. Anyway, this piece does a great job of pointing to the problematic moral grounds that Berry and the current liberal food movement rely on - nice work! Also, I haven't read much of Berry's writing in a while but have heard folks praise his evolution in thought...have you noticed any positive changes there?

Awesome! I agree with you. Though Benson and Butz appear prominently in work, I just sidestepped the whole quote affair because I never saw the quote in the primary sources and because I had plenty other juicy quotes to use.