How Twitter Explains the Civil War (and Vice Versa)

Political Violence and Communication Revolutions

Greetings, dear readers! I suspect you didn’t expect to receive another issue of The Strong Paw of Reason so soon, but I’m delighted to publish a bonus issue of the newsletter on the one year anniversary of the January 6 riot at the US Capitol, an event that has previously been the source of great intellectual ferment in this newsletter. But this issue isn’t dedicated to my intellectual ferment. Although Strong Paw doesn’t have many paying subscribers, we do have a few. And rather than using their subscriptions to deck out my garage gym, I’m dedicating those funds to publishing (and paying for) outstanding posts from writers I admire. This is the first of those guest posts, and it’s a damned doozy that is perfect way to commemorate the ignominy of January 6.

Let me briefly introduce its author, my friend Ariel Ron. Ariel is a history professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas who writes about politics and economics in nineteenth century America. He is one of a group of young historians whose erudition and brilliance is responsible for making agricultural history simply the sexiest historical subfield on the block (admittedly, a frightfully low bar). He is the author of the blockbuster Grassroots Leviathan: Agricultural Reform and the Rural North in the Slaveholding Republic, which won awards from the Agricultural History Society and Center for Civil War Research, and is a pivotal reinterpretation of the road to the US Civil War. He’s held all the fellowships, published in all the journals. And because he can kill you with his jumper (historical) and his crossover (contemporary), he also does occasional policy consulting in the alternative protein space. Most importantly of all, he’s a killer DJ (seriously) and I’m listening to his latest techno mix as I type this. Follow him on Twitter. Take it away, Ariel!

The attack inside the U.S. Capitol building was unexpected and shocking. Images of the bloody encounter circulated widely, inundating newspapers and other media, causing a sensation. The politician responsible was soon out of office but his supporters continued to back him unreservedly, touting what his detractors called a crime as proof of his mettle.

The year was 1856. A member of Congress had just beaten another near to death. Preston Brooks, a representative from South Carolina, brutally caned the antislavery Massachusetts senator, Charles Sumner, as he sat at his desk on the Senate floor. It would take two years for Sumner to recover. Brooks resigned under the threat of censure only to be resoundingly reelected. Five years later, Union and Confederate armies were massing.

That the shocking spectacle of political violence inside the halls of Congress brings to mind the events of January 6 suggests why people keep reaching for the Civil War to describe the current state of American politics. Historical analogies are tricky and often superficial. But if you go past familiar textbook narratives to look at the deep roots of Sumner’s violent encounter with Brooks, you can find surprisingly familiar social changes that might offer some useful lessons.

In the decades leading up to the war, the United States underwent a profound communications revolution that altered how Americans connected with one another. It was a historical development that bears uncanny resemblance to our current moment. The Twitterfication of public life and other broader changes to the mediascape are again fostering strange and dangerous political shifts. Although Internet 2.0 differs in countless ways from its antebellum media ancestors, it illustrates how media that were once novel—newspapers, lithographs, sheet music, and other kinds of mass print—could upend traditional politics and create space for the new configurations that make violent ruptures possible, maybe inevitable. In other words, a generation into the internet age, we’re well placed to see key patterns of political disordering in a another period.

How did new print media upend politics? Mainly in two ways, both of which seem also to be happening today. First, they curtailed political leaders’ control over what got talked about in public. That is, they sapped politicians’ power to set the agenda. Second, new media scrambled the existing channels of information flow, forcing politicians to recalibrate how they pitched themselves to different constituencies. The result was a breakdown of the system of party coalitions that had underwritten, for thirty agonizing years, slavery’s expansion across the Deep South.

[Media coverage of Sumner’s caning included several lithographic representations such as these. Far more versatile and cost-effective than engravings, lithographs revolutionized American graphic culture during the antebellum era. They added a new kind of vivid immediacy to written descriptions of major events and trends. Note how the image on the right skillfully deploys visual language to and captioning to deliver a powerful argument. Bufford, J. H. & Homer, W. (1856) Arguments of the Chivalry, 1856. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress; Magee, J. (1856). Southern chivalry - argument versus club's [Print]. Retrieved from Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth.]

The roots of the antebellum party system lay with an even earlier political crisis that shattered the so-called “Era of Good Feelings.” In 1819, Congress was considering legislation to enable the territory of Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state. But the New York congressman, James Tallmadge, objected. He introduced an amendment to the bill that would have gradually ended slavery in Missouri. This move touched off a political blaze that burned for two years, as southern and northern members of Congress furiously debated the merits of slavery. Thomas Jefferson famously compared the crisis to a “fire bell in the night,” a moment that filled him “with terror” because it tolled the death “knell of the Union.”

The thing that made the dispute so incendiary was that some northern and southern politicians began to marshal their constituents at home, potentially transforming a dispute among the elite into a division of the American people. Nearly all the basic talking points for and against slavery that appeared during the runup to the Civil War, forty years later, were already being aired at this time. But Congress ultimately compromised. The deal that was struck enshrined the principle of parity for slaveholders in the Senate and drew a line across the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase separating future free states from future slave states.

Yet who was to say the truce would hold? A deeper compromise was necessary. Enter another New York politician, Martin Van Buren. In support of Andrew Jackson’s 1824 presidential run, Van Buren constructed a national alliance “between the planters of the South and the plain Republicans of the north,” as he explained in a letter to the Virginia politico and newspaper editor, Thomas Ritchie. Van Buren’s concept was simple. If northerners and southerners coalesced as a disciplined political party, they would depend on one another to win elections, especially the presidency. This would bind them to the principles of the Missouri Compromise, even if it meant agreeing to disagree about slavery itself. The coalition was christened the Democratic Party and its electoral success soon spawned a rival North-South coalition, the Whig Party.

So long as the Democrats and Whigs each depended on both northern and southern voters, political leaders had a tacit incentive to collaborate in downplaying the divisive matter of slavery. But because slavery was, in fact, divisive, it was often necessary for politicians to say one thing at the national level and another thing back home in their districts. This was doable so long as the national mediascape remained regionalized and well in the hands of party leaders. But already in the 1830s, disruptive changes were underway.

The changes can be traced back to the federal government’s early commitment to disseminate information about the public business. The way this worked was that the Post Office subsidized newspapers with low rates. Free exchanges, which allowed small country sheets and large city dailies to swap papers and thereby keep abreast of doings everywhere, leveraged the subsidies into a national information network. The expansion and segmentation of this network would ultimately spell trouble for Van Buren’s strategy, but initially it served his purposes.

During the political battles that preceded the misnamed Era of Good Feelings, newspapermen emerged as central players. Some of them, like Ritchie, then became powerbrokers in the Van Burenite party system. Party competition was great for the newspaper business. Localities that could not financially support even one regular paper got two, each an organ for, and beneficiary of, a major party. A press with this structure allowed party leaders to tailor their messages for electoral gain and policy cohesion. Some issues, like those concerning fiscal and monetary policy, were nationalized, while others, like slavery, were kept local. It could then appear that slavery was a “peculiar institution,” that is, an issue that concerned only those directly involved, into which the federal government ought not to stick its nose.

But some people thought that slavery was a moral abomination. They were committed to ending it wherever it might be. By the early 1830s, black and white abolitionists in the North had grown well-organized and well-funded, allowing them to initiate two deceptively consequential advocacy campaigns. In the first, they printed tens of thousands of antislavery tracts and cold-mailed them to business and community leaders throughout the South. Their aim was to persuade powerful southerners of slavery’s sinfulness and the need to change course immediately. The effect was quite the opposite. Southern postmasters interdicted and burned the abolitionist mails, in violation of federal law but with tacit approval from federal administrators and members of Congress. Meanwhile, enslavers doubled down on the defense of enslavement. They called it a “positive good” that stood at the very foundation of civilized society—a move not so different in form from many conservatives’ insistence today that their values alone made America great.

The abolitionists’ second campaign was savvier. They coordinated a mass petition drive that deluged Congress with demands to end slavery in the District of Columbia, where it had indisputable Constitutional authority to do so. To dodge this effort, politicians resorted to the infamous “Gag Rule.” For nearly a decade, at the start of each session of Congress, Whigs and Democrats agreed to table abolitionist petitions without reading them, preventing their entry into the public record. Nothing better demonstrated the party system’s imperative to suppress any intimation of conflict over slavery at the national level.

Yet the very existence of the abolitionist campaigns hints at a changing mediascape that would soon evade party leaders’ control. Abolitionism’s new militancy originated with black activists such as David Walker, who penned a fiery and influential antislavery pamphlet in 1829 that was disseminated widely by black sailors. The movement grew with the founding of the first long-lasting abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831. Taking advantage of postal subsidies for all papers regardless of content, The Liberator built a dedicated subscriber base far beyond its Boston home. Funding for the mail and petition campaigns came from businessmen who, among other ventures, had founded the first credit reporting service in America—a most useful experience in the long-distance collection and transmission of information. Abolitionists learned to use the new media skillfully. The Gag Rule, for instance, barred them from Congress but itself became a news item that they used to stoke controversy and debate.

For all their sophistication, abolitionists experienced the 1830s as a time of trial. They remained a small minority within northern society and their advocacy campaigns had been quashed. Simultaneously, they were violently attacked by anti-abolitionist mobs that, in one notorious case, murdered the abolitionist minister and printer, Elijah Lovejoy. Yet these very defeats gained abolitionists a rising undercurrent of northern public sympathy. The censoring of the mails, the gagging of the petitions, and the asaulting of antislavery speakers disquieted many northerners who increasingly defined themselves as participants in a media culture that prided itself on the free exchange of knowledge and opinion.

A key feature of this media culture was the segmentation of the print market that followed from northern population growth, economic development, and near-universal literacy, along with a proliferation of printing techniques and technologies that emerged in a feedback loop with print culture itself. Much like today, the mediascape suddenly blew up with new forms and contents. Whereas in the 1820s the vast majority of newspapers stuck to mainstream political and commercial news and had an affiliation with one of the two major parties, by the 1830s the print market was a great deal more diverse. On the one hand, the large urban dailies had become a “penny press.” Their business model was low-cost, high-volume sales, which encouraged coverage of stories not previously considered newsworthy, such as salacious sex and murder scandals. On the other hand, a slew of religious, commercial, agricultural and other specialized periodicals appeared. The combined effect was to greatly expand the range of public discourse in print.

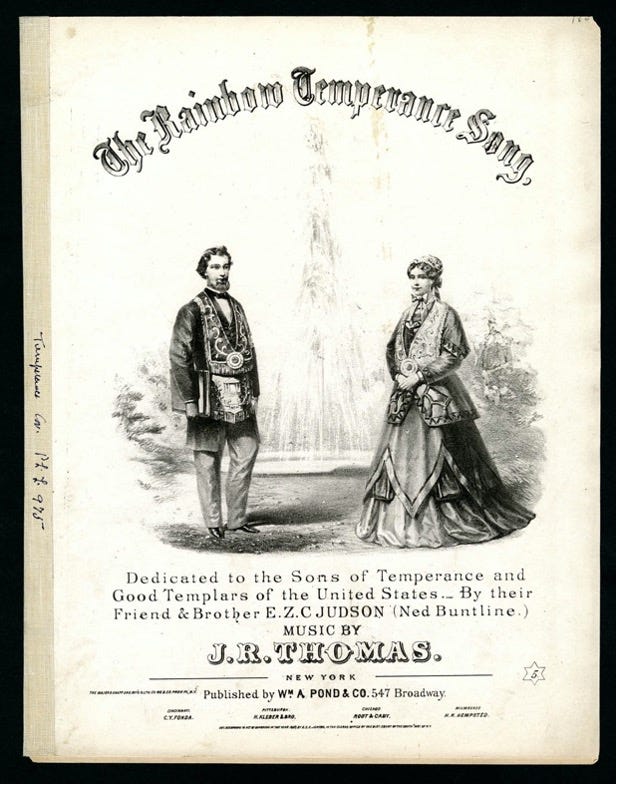

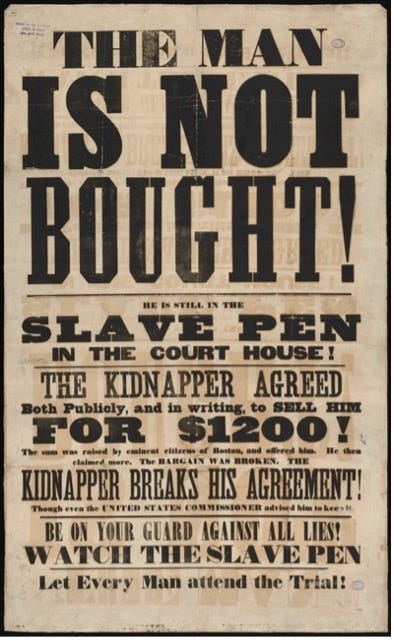

A more subtle effect was the creation of new sub-publics around distinct print niches. The rise of the farm press in the 1830s and 40s, for instance, catalyzed a mass agricultural reform movement that ultimately led to the creation of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the land-grant university complex. These were enormous changes in government policy that originated from outside the party system. As early as the 1850s, the parties were struggling to either parry or incorporate not only the abolitionists and agricultural reformers, but powerful anti-immigrant and anti-liquor movements with their own formidable publishing capacities. Even sheet music became a way to consolidate a distinct cultural identity available for mobilization.

[Every social movement needs songs. Printed sheet music made them easy to disseminate. Here, “The Rainbow Temperance Song” and the “K N Quick Step” aimed to strengthen the cohesion and commitment of supporters of the anti-liquor and nativist movements, respectively. 1866. The Rainbow temperance song. Retrieved from Share Tennessee. [Sheet music]; A.E. Jones & Co, W.C. Peters & Son & Winner & Shuster. (1854) K N quick step dedicated to the Know Nothings. United States, 1854. Philada.: Published by Winner & Shuster. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress.]

The political significance of these developments was that Whigs and Democrats lost control of the public agenda. The appearance in 1851 of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, epitomized the new realities. This record-smashing bestseller, which Abraham Lincoln half-jokingly blamed for the Civil War, began its life as a serialized narrative in the abolitionist newspaper, The National Era. Reprinted in whole or in part by other newspapers, it soon came out as a book that became an international blockbuster. Pro-slavery advocates felt bound to respond directly, rapidly publishing two dozen or more counter-novels that depicted happy slaves on idyllic plantations. The exchange, at the level of popular literature, indicates the newfound power of political outsiders to shape public discourse in the teeth of party leaders’ desires to avoid such controversial ground.

It shows something else, too. It was no longer possible for politicians to ensure that their constituents heard different messages than did the constituents of their coalition partners. The problem was never with members of Congress themselves. Since the 1820s, Congressmen and Senators had regularly delivered speeches to “bunkum” (home-district voters), which their colleagues in the Capitol studiously ignored. But with the rising density of media networks and the power of social movements to generate publicity, constituents were no longer in the dark about how other constituents, elsewhere in the country, really felt. The truly dangerous aspect of the Missouri Crisis—the marshalling of diverging mass popular sentiments on the question of slavery—had returned.

The early 1850s would prove a political free-for-all. Congress was unable to forge a durable solution when the end of the US-Mexico War in 1848 presented essentially the same dilemma it had faced with the Louisiana Territory: how to legislate on the status of slavery in a large, newly-acquired and valuable domain. Congress did pass the series of measures known as the Compromise of 1850, but they began to fail almost immediately. By 1854, they were worse than worthless, they were actively contributing to the national dissolution.

The parties had completely lost control of the narrative. The first to go down were the Whigs, whose dissolution after 1852 began not with slavery, but with alcohol. In 1851, anti-liquor advocates, who probably constituted the largest social movement in the country but had previously stuck to social rather than political activism, got Maine to pass an anti-liquor law. Alcohol now took center stage in the politics of several northern states and the result was that Whigs split down the middle. Unable to come together at the state level, the Whigs were also breaking apart at the national level as pro- and antislavery agitation drove a wedge between their northern and southern wings. In place of the Whigs, the anti-immigrant Know Nothings, officially called the American Party, suddenly rose to national prominence with stunning electoral victories in 1854. This remains one of the most astonishing episodes in American political history, as a party with genuine electoral power emerged suddenly, as if out of nowhere, from a warren of semi-secret nativist clubs and communications channels.

This formation, too, soon dissolved, and precisely for this reason it is very revealing of the disordered state of American politics during these years. It shows that the people who break the system often know not what they do, achieve only transitory power, and end up simply making way for some other group. In place of the Know Nothings, a portentous coalition of abolitionists, former Whigs and Democratic defectors gained ascendance as the dominant party in the North by 1856—consolidated, in no small measure, by the shocking caning of Senator Sumner that same year. This was effectively the end of the party system’s commitment to suppressing contention over slavery. It set the stage for secession and the outbreak of armed conflict.

[An underappreciated aspect of the communications revolution was that it made it relatively easy to print large runs of public notices very quickly. In the broadside above, abolitionists seek to publicize the arrest of Anthony Burns (pictured right) in order to prevent his return to slavery. The Burns case was a significant moment in the undoing of the failed Compromise of 1850. Below, “The Bill-Poster’s Dream” satirizes the cacophonic visual effect of jumbled public notices, suggesting the disorienting effects of the new print culture. Andrews, J. (ca. 1855) Anthony Burns / drawn by Barry from a daguereotype by Whipple & Black ; John Andrews, SC. Boston Massachusetts, ca. 1855. Boston: R.M. Edwards, printer, 129 Congress Street. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress. The man is not bought! [Ephemera]. (1854). Retrieved from Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth. Derby, B. The Bill-Poster's dream [graphic] : cross readings, to be read downwards. New York : B. Derby, 1862. Retrieved from the American Antiquarian Society.]

The historical sequence that culminated with the Civil War and the destruction of U.S. slavery was therefore very much conditioned by the period’s media revolution. The explosion of print-based formats and causes first enabled and then disrupted a political system that, for about thirty years, gave party leaders the power to position the issues of the day. They used that power to disguise the moral and political disaster that was antebellum bondage. But with new means to speak in public via print, Americans raised a host of new concerns which, diverse as they were, effectively teamed up to undo the old order and create space for the new. Eventually, most Americans realized that they could no longer agree to disagree about slavery.

This way of narrating the coming of the Civil War reflects an Internet-age perspective. Viewing antebellum history from a perch in the Twitterverse, it becomes easy to see the proliferation of antebellum print as essentially analogous to our own tectonic shifts in how people communicate and what they communicate about. Today’s social media and the ever-finer segmentation of news provision are assembling masses of people who care deeply about things that other masses of people find to be alternatively crazy, irrelevant, thrilling, inspiring, appalling and bizarre. This cannot fail to have transformative political consequences down the road because the redrawing of communicative social ties is equally a redrawing of communicative social tensions. By altering the material means and cultural modes of collective life, the new media are inevitably fracturing received political structures and creating unpredictable openings for novel ones to emerge.

QAnon is the superlative example so far. Activists have been using social media to organize and sustain extremely powerful protest movements since at least the Arab Spring broke out a decade ago. The new communicative strategies have clearly shaped these movements. Black Lives Matter, for example, was repeatedly criticized by older generations of activists for its lack of recognizable leadership and organizational structure, but its loosely networked configuration proved itself when the murder of George Floyd spawned a seemingly spontaneous nationwide uprising. QAnon, however, seems a phenomenon of a different order. It has apparently enveloped many, many people in a totalizing mediaverse that is as much a new cultural pattern as a new political one. Its messianic linkage to the first Twitter president really puts it in a class of its own.

The political potentialities of the evolving IT mediascape lie in this capacity not just to provide new tools for longstanding struggles, as with BLM or the Arab Spring, but to entirely reconfigure the cultural field on which politics plays out. Take the hashtag campaign, #MeToo. Though it clearly built on the long-standing feminist strategy called consciousness-raising, the speed, power and shape of its wave were unprecedented. Most distinctively, it made Twitter and other platforms the ground for exerting pressure on prosecutors, employers, university officials and others to take action. It was surely a major contributor to the panic over “cancel culture” that has now morphed into the weird fixation on Critical Race Theory.

More intriguing is the potential for mobilizing fandoms. A fundamentally Internet-based cultural formation, fandoms arise from webpage formats like messaging boards and wikis that are basically open to anyone but are minutely subdivided by area of interest, especially with respect to celebrities, TV shows, video games, music genres, culture industry franchises, and so on. Fandoms are loose associations of dedicated media consumers whose passionately nerdy discussions evolve into mini-online subcultures. Seemingly miles away from politics, these groups can become politically activated. This happened, for instance, when K-pop stans (fans of Korean pop music), registered en masse for a 2020 Trump campaign rally, only to no-show and embarrass the president with an empty arena. At a deeper lever, the Gamergate saga shows how seemingly arcane cultural spats can orient the politics of huge groups of people.

Somewhat similar was the swarm of small investors who pushed up Gamestop shares after collectively strategizing on the subreddit, r/wallstreetbets. Although the action had no programmatic political content—just a vaguely anti-elitist rhetorical stance—it is easy to imagine how the eventual policy response from the Securities and Exchange Commission could set off a genuine activist movement among self-identified “retail investors” who coordinate via subreddits, memes, hashtags and the like. Were this to happen, action would be crucially conditioned by the specific cultural sensibilities that Internet-based communication is daily making a real factor in the exercise of social power. And the ramifications could become unpredictable if changes to rules and market behavior were significant enough to affect macrolevel financial arrangements no one had previously thought at stake.

Predicting where all this goes involves identifying what deep structural conflicts have been suppressed by the political order that is now faltering. For the antebellum period, the answer is very easy. It was the division between free and slave states, which generated all kinds of frictions that Democrats and Whigs worked cooperatively to deflect. Thomas Jefferson sensed from the start that it was a doomed effort. In 1820, reflecting on the “fire bell” of the Missouri Crisis during a temporary lull in the fracas, he wrote to a friend: “A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.”

Whether the ultimate breakup of the Union over slavery was really inevitable is hard to say. History cannot be run back. But the movement by northern states to abolish their own enslavement regimes after the American Revolution undeniably began to etch a “geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political.” While the chasm deepened, the two-party compact acted like a canopy that hid it from view. Only in the 1850s did the cover become so riddled with holes that if finally collapsed and vanished into the abyss below. At that point Lincoln was right to say that “this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. . . . It will become all one thing or all the other.” And so it did.

That hardly means we are headed toward something like a civil war, which seems to me unlikely. There is no equivalent today for the circumstance that so terrified Jefferson: the coincidence of a stark structural divide with a sectional geographic one. What we have instead are stacked divergences splitting metropolitan areas from their exurban-rural hinterlands. On the one hand, the structural aspects of this divide do not approach the depths of the problem posed by slavery. And on the other hand, the geographic aspect, despite the phenomenon of partisan sorting, makes for a patchwork of political conflicts in every region of the country rather than a polarization of two large and contiguous sections. Interestingly, this may finally spell the end of southern distinctiveness within the American polity. As southern metro areas, especially in Texas, Georgia and North Carolina, grow increasingly liberal and clash head on with more conservative state governments, their politics will align with and model national patterns.

As a political matter, slavery was unique in American history and has had no real parallel. That is precisely what makes the Civil War analogy apt today. Not because we are doomed to repeat the same devastating catharsis, but rather because the sheer starkness of the structural conflict at the heart of the Civil War era clarifies the power of the ingenious political suturing that kept conflict over slavery concealed and inoperative for more than a generation. It should not be taken for granted that this suturing was finally undone. Likewise, the chaotic agency of a communications revolution, then, as now, should not be underestimated.