Political Prediction as Humiliation Kink

Ross Douthat and Conservatism's Unspeakable Political Desires

The United States is hurtling towards a fiery political crisis. I have yet to hear any smart person explain how it’s going to resolve without serious and sustained political violence. Comes now Ross Douthat to reassure us that everything is just fine because the pre-Trump Republican establishment will do something it has as yet failed to find a way to do in the past six years: reassert control over the party and meaningfully constrain Trump’s bullying excesses. Because, after all, he failed last time and, surely, his grip on the GOP is waning? Right? Right?!

Douthat’s argument is that the “deadly futility” of the January Capitol Riot “illustrated Trumpian weakness more than illiberal strength” since it showed the institutional GOP would refuse to back Trump’s authoritarian ambitions when the chips were down. What this interpretation fails to recognize is that Trump failed in January 2021 not because “the GOP establishment” did very much—herald of responsibility Mitch McConnell refused to acknowledge Trump’s efforts to overturn the election until the riot itself called his hand—but because a tiny sliver of elected GOP officials entered into a temporary alliance with an absolutely unified Democratic party. To change the dynamic more favorably to Trump from where it was in January 2021 doesn’t require a whole new Republican party, just some tinkering. It requires merely purging enough of those few elected GOP officials to remove them from the machinery of power and, by example, to bring any potential future dissenters sharply to heel. Not surprisingly, this is precisely what the Trumpkins have been up to in the past few months and what will likely continue to be their resolute focus as long as Trump is their figurehead.

Douthat’s writerly voice always strains to convey sober-minded realism. He is even cautious about caution, telling us that the “worriers” are not so much “unreasonable” as “extremely premature.” His perspective is delusional in the cliched, if not clinical sense: doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results. At every step in Trump’s rise, “reasonable” Republicans have sniffed about Trump’s authoritarianism and have done absolutely nothing of substance to contain it. This is because they do not recognize Trump’s authoritarian impulses as their own, cannot see that his racism, crass materialism, phony concern for the poor, superficial religiosity, casual cruelty, nationalist zeal, and glib disregard for community have been mainstays of the Republican party for a half century.

Trump perfected Republicanism. He wasn’t its ego, no—he didn’t walk, talk, or look like it—but he saw its desires and he served up a big tasty slice. Trump stormed the party by giving its voters exactly what they wanted—indeed, probably what Douthat has always wanted but is afraid perhaps to admit. Douthat cannot see this because that would require he reckon with the ugly reality of his own political community and the actual material legacies of the conservative politics he is trying to repackage. One thing that unites Douthat’s voice and political analysis is that he seems utterly terrified by his own desires, which is precisely why the sobriety of his voice is always ever so slightly trembling and his writings about sexuality, a topic he returns to frequently, are so cringeworthy, if hilarious. If you are fundamentally terrified of your own desires and the loss of control they might impel, you will treat the problem of sexuality only ever as a disembodied abstraction, to be calculated and quantified, to be rendered standard and fungible. But you must never talk about it as a quality or experience, because the experience of sex is often about vulnerability, irrationality, and a lack of sobriety. You will, instead, write columns like this, perfectly illustrating the mode of thought of what I refer to as “The Sex Accountant.”

But I digress. You need not take my word for this analysis. We can stroll down memory lane. And so, in today’s issue of Strong Paw, I give a rough and ready intellectual history of Douthat’s analysis of Trumpism during its embryonic phase, the period between roughly 2012 and summer 2016. By summer 2016, it was clear that Trump would be the GOP nominee, after which point predictions about how the Republicans will respond to him begin to lose their meaning. It is more interesting, and far more revealing, to observe how Douthat responded as Trump surged into the Republican party, because it shows us much about Douthat’s insights—and delusions—about the nature of Trump’s appeal to his supporters and how and why Douthat continues to underestimate and misunderstand Trumpism.

By contrast, I am only bragging a bit when I say that I have never underestimated Trump, despite the fact that I generally have a much dimmer view of him as a person, an intellect, and a leader than Douthat. I correctly identified Trump as a likely GOP nominee after his first debate performance in late summer of 2015. I was able to to do this because I saw clearly then what Douthat has never been able to see: Trump is an expression of American conservatism and its authentic avatar and banner carrier. Douthat’s inability to recognize Trump as an expression of conservative political strategy results in confused, misfiring, and incoherent analysis. As you will see, Douthat alternated between noting that Trump was a zany, wacky, outrageous demagogue and, at once, reassuring his readers not to trouble themselves about it because the ever-so sober and not actually authoritarian-curious Republican party would never endorse such madness. The zig-zag was disorienting, bordering on comical. One can sense the arousal, even admiration for Trumpian political excess—”a politician who will finally give us… I mean them what they want!”—followed by Douthat’s ego shushing all the wicked fun by soberly intoning that somehow, somewhere the cooler heads would prevail. Again and again. Trump offers to give him what he wants, Douthat reaches the edge, only to pull back at the last moment, an endless series of deferrals and denials. Douthat, always the bungler about sex, has never realized that to those who desire to be edged, everyone else is “extremely premature.”

Let’s begin in March of 2012. Here’s Douthat’s reflections on the GOP Presidential primary’s resolution in favor of Romney:

From early 2011 onward, the media have overinterpreted this sifting process, treating every polling surge for a not-Romney candidate almost as seriously as an actual primary result. They might nominate Herman Cain! They might nominate Michele Bachmann! Why — they might nominate Donald Trump!

Not so much. Instead, despite an understandable desire to vote for a candidate other than Mitt Romney, Republicans have been slowly but surely delivering him the nomination — consistently, if reluctantly, choosing the safe option over the bomb-throwers and ideologues.

A crazy party might have chosen Cain or Bachmann as its standard-bearer. The Republican electorate dismissed them long before the first ballots were even cast.

So Trump is an option that Douthat includes among the “bomb-throwers and ideologues” that a “crazy party” might select. He concludes that the dalliances with those sorts—the sustained interest in Michelle Bachman, for instance—did not indicate there was any genuine interest in authoritarian leaders, but, instead, that the GOP was “less a party gone mad than a party caught between generations.” He then offers us this helpful counterfactual: “If it were being held two years hence, and featured Chris Christie, Bobby Jindal, Paul Ryan and Marco Rubio, the excitement on the Republican side would rival what the Democrats enjoyed in 2008.” [Sad trombone noise.]

In fact, Douthat would have to wait three years to test this proposition, when Christie, Ryan, and Rubio all launched their presidential campaigns. And, of course, so did Trump. Let’s see what Ross had to say then. In a column from August of 2015 in which he names Trump “deliberately outrageous,” he confidently asserts, “Trump won’t be the Republican nominee, but the eventual nominee may end up owing him a debt of gratitude for services rendered along the way.” And who will Trump serve? Who will the ever-reasonable Republican voters gravitate towards? Why Jeb Bush, of course. [Louder sad trombone noise.]

Later that very month, Douthat suggests that Trump’s popularity should be understood as an expression of populist anger, particularly on immigration, that cannot find a “healthy” outlet through either the GOP or Democratic Party. Then he writes this:

Because he knows Wall Street, and because he doesn’t need its money to campaign, it seems like he could actually fight his fellow elites and win.

He won’t, of course, but it matters a great deal how he loses. In a healthy two-party system, the G.O.P. would treat Trump’s strange success as evidence that the party’s basic orientation may need to change substantially, so that it looks less like a tool of moneyed interests and more like a vehicle for middle American discontent.

In an unhealthy system, the kind I suspect we inhabit, the Republicans will find a way to crush Trump without adapting to his message. In which case the pressure the Donald has tapped will continue to build — and when it bursts, the G.O.P. as we know it may go with it.

Once again, that Republicans will “find a way” to stop Trump is taken for granted, as is the idea that Trump represents impulses that are fundamentally alien to the currently constituted Republican party or, to the extent that they are found there, they will be disciplined by the party’s elders. The latter is so taken for granted that Douthat concludes that the Republican party cannot be taken over by Trump, but can only be destroyed by him. [Louder, longer, sadder trombone noise.]

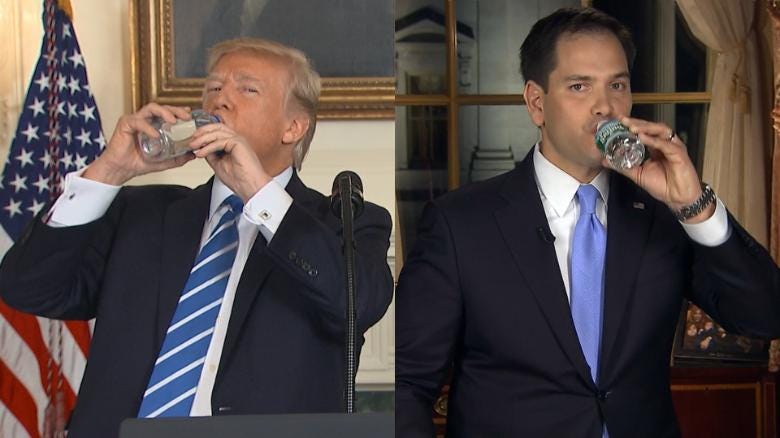

By October of 2015, however, Douthat was still struggling to figure out how the party elders were going to do this “crushing.” Who would be the vehicle? Douthat exuded an ambient awareness that no one seemed to be mustering the vigor to take on Trump directly, but he couldn’t bring himself to the obvious conclusion that Trump, then leading in the polls and dominating the debates, was the front-runner. Such a conclusion might have led him to revise his assumptions about what Republicans truly desired, but, alas, he concluded instead, “No major party has ever nominated a figure like Trump or Carson, and I don’t believe that the 2016 G.O.P. will be the first.” The front-runner had to be someone else, anyone else, and Douthat’s intellectual task was to sort the wheat from the chaff and, through “the elimination game,” he designated Marco Rubio to be the front-runner. Reasoning by process of elimination in this way is often a sign of magical thinking, and this was, of course, exactly how the entire Republican establishment dealt with Trump: let Trump eliminate his rivals one by one until you could rally around the final survivor. Oops. [Louder, longer sad trombone noise.]

You won’t be surprised to learn that the “lumbering beast” of the GOP establishment, as Douthat called it in December of 2015, never figured out how to deliver on the promise to “crush” Trump. In that column, Douthat pondered if Trump was a fascist, coming to the characteristically milquetoast equivocation that Trump was “not a fascist” but, rather, “closer to the proto-fascist zone.” What a useful distinction! And should this be a source of alarm perhaps? Douthat’s ego quickly quashed all those nasty anxieties. It’s worth quoting at length:

I would say no, for three reasons. First, Trump may indeed be a little fascistic, but that sinister resemblance is just one part of his reality-television meets WWE-heel-turn campaign style. He isn’t actually building a fascist mass movement (he hasn’t won a primary yet!) or rallying a movement of far-right intellectuals (Ann Coulter notwithstanding). His suggestion that a Black Lives Matter protester at one of his rallies might have deserved to be roughed up was pretty ugly, but still several degrees of ugly away from the actual fascist move, which would require organizing a paramilitary force to take to the streets to brawl with the decadent supporters of our rotten legislative government.

Second, precisely because Trump doesn’t have many of the core commitments that have tended to inoculate conservatives against fascism, it’s still quite likely that the Republican Party is inoculated against him. His lack of any real religious faith, his un-libertarian style and record, his clear disdain for the ideas that motivate many of the most engaged Republicans — these qualities haven’t prevented him from consolidating a quarter of the Republican electorate, but they should make it awfully difficult for him to get to 40 or 50 percent. And a somewhat fascist-looking candidate who tops out where Trump’s poll numbers are currently hovering is not something to panic over — yet.

Finally, freaking out over Trump-the-fascist is a good way for the political class to ignore the legitimate reasons he’s gotten this far — the deep disaffection with the Republican Party’s economic policies among working-class conservatives, the reasonable skepticism about the bipartisan consensus favoring ever more mass low-skilled immigration, the accurate sense that the American elite has misgoverned the country at home and abroad.

It’s all just an act, so enjoy the show! And the GOP is inoculated against him… for some reason I can’t really explain! And, anyway, saying out loud that he’s a budding authoritarian would require us to admit that certain policy hobby-horses of Ross Douthat do, indeed, frame national belonging in a way that is highly conducive to authoritarian demagoguery. [Louder, longer, saddest trombone noise.]

I suppose I agree with Douthat that a substantial portion of Trump’s appeal was that he staked out rhetorically and substantively a starkly nativist and racist position on immigration. Douthat would return to this point again later in the month, this time to hopefully speculate that it would be Ted Cruz, not Jeb! or Little Marco, who would finally confront Trump. The problem, of course, is that Douthat offered no self-reflection on why the GOP’s long-standing servility to global capital has generated a racist immigration backlash within the party rather than, say, an effort to meaningfully regulate capital. In fact, Douthat’s preferred solution to this racist immigration backlash—how to defeat “Donald Trump’s fascistic forays”—was essentially to give into it. That is, rather than regulating the operation of capital in the United States in ways that represent the interests of workers burned by the neoliberal consensus, Douthat preferred a Republican party that imposed greater controls on and then fundamentally fractured labor. For example, this is precisely the arrangement that California’s growers, fervent Trumpkins and immigration restrictionists, sought to impose again and again in the past half decade. Douthat’s solution to Trump’s fascism was to sublimate and disavow it through immigration policies that select and maintain a class of workers denied full political citizenship and deemed socially disposable. In other words, the solution to Trump’s fascism was to shove it some place where Douthat didn’t have to be reminded of it all the damn time. Ah, Douthat, always the killjoy. There’s no fun in that! The whole point of Trump is not just giving into your most base, selfish desires; but doing so proudly for the whole world to see. [One long, loud, bleak fucking trombone noise.]

By January, Douthat was explicitly embracing the Catholic confessional, without apparent irony or self-awareness, to be forgiven for “underestimating” Trump. After a series of not entirely persuasive self-justifications for his error, we got to the nut of the matter:

Now if I wanted to avoid giving Trump his due, I could claim that I didn’t underestimate him, I misread everyone else — from the voters supporting him despite his demagoguery to the right-wing entertainers willing to forgive his ideological deviations.

Indeed. One could say that Douthat not only never knew the company he kept, but that he never really knew himself until he confessed his sins on the opinion page of the New York Times. Lest you think this confession of miscalculation brought him to some heightened awareness of his own desires that might forestall future mistakes, he concluded with this:

Of course I’m not completely humbled. Indeed, I’m still proud enough to continue predicting, in defiance of national polling, that there’s still no way that Trump will actually be the 2016 Republican nominee.

Trust me: I’m a pundit.

(And I’ll see you in the confessional next year.)

Ah! Well, nevertheless, Douthat was prepared to confess again the same time next year and we might casually wonder if some perverse psychodynamic was at play here. Recall of course that the confession is a practice, according to Foucault, marked by “spirals of power and pleasure.” Allegedly, Douthat has read Foucault. [Short, sharp flatulence-like trombone noise.]

Right on time, Douthat returned six days later, on January 7, to reassure his readers once again, “Donald Trump isn’t going to be the Republican nominee.” The column is a memorable exercise in political fantasy, with Douthat speculatively dancing among dozens of finely tuned electoral factors and constituencies to land, ever so nimbly, on precisely the conclusion that his last column should have warned him against: Trump can’t win! He maintained this position for just about two weeks, before he then swung, on January 23, to smugly explain to readers how to “stop Trump.” It begins with extended jaw-dropping snark, in which Douthat sarcastically derides anyone who has the temerity to say the obvious: Republican voters were making their choice and their choice was Trump. Back when I was a college debater, we joked that you knew someone was losing an argument badly when their only mode of rebuttal was to “repeat your argument back to you but in a funny voice” and that’s essentially what Douthat does:

This is, of course, a pointless column. The Republican presidential race is over, as you may have heard. Donald Trump has the nomination wrapped up — in the most luxurious, velveteen packaging you’ve ever seen. You’ve seen his polling lead: It’s yuge. You’ve watched his rallies: They’re even yuger. You’ve heard from the insiders, the panjandrums, the grand poo-bahs: He’s a man they can do business with; Bob Dole guarantees it. You’ve heard from Sarah Palin, and when has her political judgment ever failed?

But just in case at some point over the next few months of voting (a mere technicality, but you have to let the people have their fun), one of Trump’s remaining rivals (I can barely remember their names, to be honest) wanted to waste money running attack ads against him (a strange, antiquated concept, I know), it seems worth suggesting some ideas for how the poor hapless dear might go about it.

I think he might be being sarcastic, guys! In any case, the way to stop Trump, it turns out, was quite simple, according to Douthat. Instead of talking about (or coopting) his policies, which didn’t seem to be working and one notes was, of course, Douthat’s prior advice, one needed to attack “his brand”: “[H]ow do you flip a salesman’s brand? You persuade people that he’s a con artist, and they’re his marks.” I cannot muster prose sarcastic enough to capture my contempt for the delusional inanity of this suggestion. [No. No trombone. He doesn’t deserve the trombone this time.]

As the primary wore on, the denialism in Douthat’s column came increasingly to resemble the political analysis equivalent of the famous Onion article, “Why Do All These Homosexuals Keep Sucking My Cock?” January 28’s “Why isn’t Marco Rubio winning?” might have been helpfully retitled “Why don’t I understand the political movement I am ostensibly an expert on?” Indeed, flights of fantasy and an inability to reflect on ones own repressed desires appeared prominently again on March 12, when Douthat entertained the idea that the Republican establishment should match Trump’s theatrics by setting aside his primary victories at the convention. Trump, Douthat now soberly claims, is “an authoritarian, not an ideologue . . .No modern political party has nominated a candidate like this; no serious political party ever should.” The solution to this authoritarianism? Replacing the will of voters with party elders! Douthat doesn’t object to letting the daddies do the deciding; he just objects to the particular daddy Trump. By the end of the month, Douthat was back to the predictions game, declaring that, one way or another, Trump had sundered the Republican party and ignited a disastrous civil war. Again and again, the possibility that Trump was giving GOP voters—and Douthat—what they always desired appears as a tantalizing wisp, never fully materializing, but never entirely absent: Republicans must reject Trump’s sensationalism and authoritarianism by igniting a sensational civil war that will stomp on the will of Trump’s voters. For the slightest moment in his March 5 column, Douthat edged into an awareness of all this, writing of authoritarian demagogues, “They promise a purgation that many people at some level already desire, and only too late do you realize that the purge will extend too far, and burn away too much.” [The trombone is now on SSRIs.]

With Trump’s victory assured and his opponents broken, Douthat’s analysis by May had turned from predicting Trump’s demise to fecklessly arguing the case that Trump was no true conservative. Even then, he downplayed and underestimated the dangers Trump posed, asserting, “Trump would not be an American Mussolini; even our sclerotic institutions would resist him more effectively than that.” In his next column, he laid the blame for Trump’s victory at the feet of a political establishment too divided and disorganized to effectively resist: “The narcissism of small differences, in other words, led both the professional establishment and the professional base to surrender to a force that they had countless ideological and pragmatic reasons to oppose.” He concluded that column by weighing the possibility that Trumpism might permanently occupy a space in the Republican party, a thought he entertained by analogy to the 7th century Near East:

[I]t’s possible that the establishment and the Tea Party are more like Byzantium and Sassanid Persia in the seventh century A.D., and Trumpism is the Arab-Muslim invasion that put an end to their long-running rivalry, destroyed the Sassanid Dynasty outright, and ushered in a very different age.

No doubt many thought at first that those invaders were a temporary problem, an alien force that would wreak havoc and then withdraw, dissolve, retreat.

But a new religion had arrived to stay.

Again, to Douthat, Trumpism was foreign and Other, not an organic expression of the antidemocratic and authoritarian impulses common to American conservatism throughout its history. Rather than taking the opportunity of Trump’s authoritarian appeal to make a case for a serious reinvestment in substantive universal democracy in America, policies that would require Douthat to take seriously what progressives have been saying for decades about anti-democratic GOP voter suppression tactics, instead, Douthat, once again, invested in empty appeals to the decency, honor, and concern for national wellbeing of his fellow conservatives. Could they not see that Trump was conning them? I doubt it. More precisely, Douthat could still not see that the biggest confidence job of all was the one he was pulling on himself. [Sad trombone noise cut short by the staccato rat-a-tat-tat of the firing squad.]

As I researched and wrote this issue, I was, at first, amused by Douthat’s compulsively flawed predictions. In each column, Douthat would summon the same knowing confidence, only for the reality of the Trumpkin juggernaut to make him a fool all over again. The distance between Douthat’s confidence in his own predictions and his dismal record of accuracy heightened the comedy. I saw each column playing out in an elementary school classroom. Douthat, the teacher’s pet, would freshly straighten his bow-tie, pat down his cowlick, and eagerly raise his hand to summon teacher’s adoring attention—I know the answer!—and, then, just as all the eyes in the class are upon him, a Nelson Muntz-like Trump would shove his face into a dog-turd pie. The variety and extent of humiliations was inspiring, then encyclopedic, then exhausting. I began to wonder: How did Douthat continue to write? How had his record of missteps not shamed him into silence? It was inspiring. It was heroic. It was perverse. It was pathological.

I have mixed feelings about Mad Men, but one thing it nailed was a deep truth about advertising: the salesman doesn’t sell the product, he sells desire. If he is deft and clever, he associates his product with the desire. Douthat was correct that Trump initially approached politics as a salesman. But Douthat does not understand the physics of salesmanship, because Douthat does not understand the physics of desire, what Republicans desire, much less who or what he, Ross Douthat, desires.

This article is satisfying.