The Food System Paradox

Introducing Feed the People!: Why Industrial Food Is Good and How To Make It Even Better

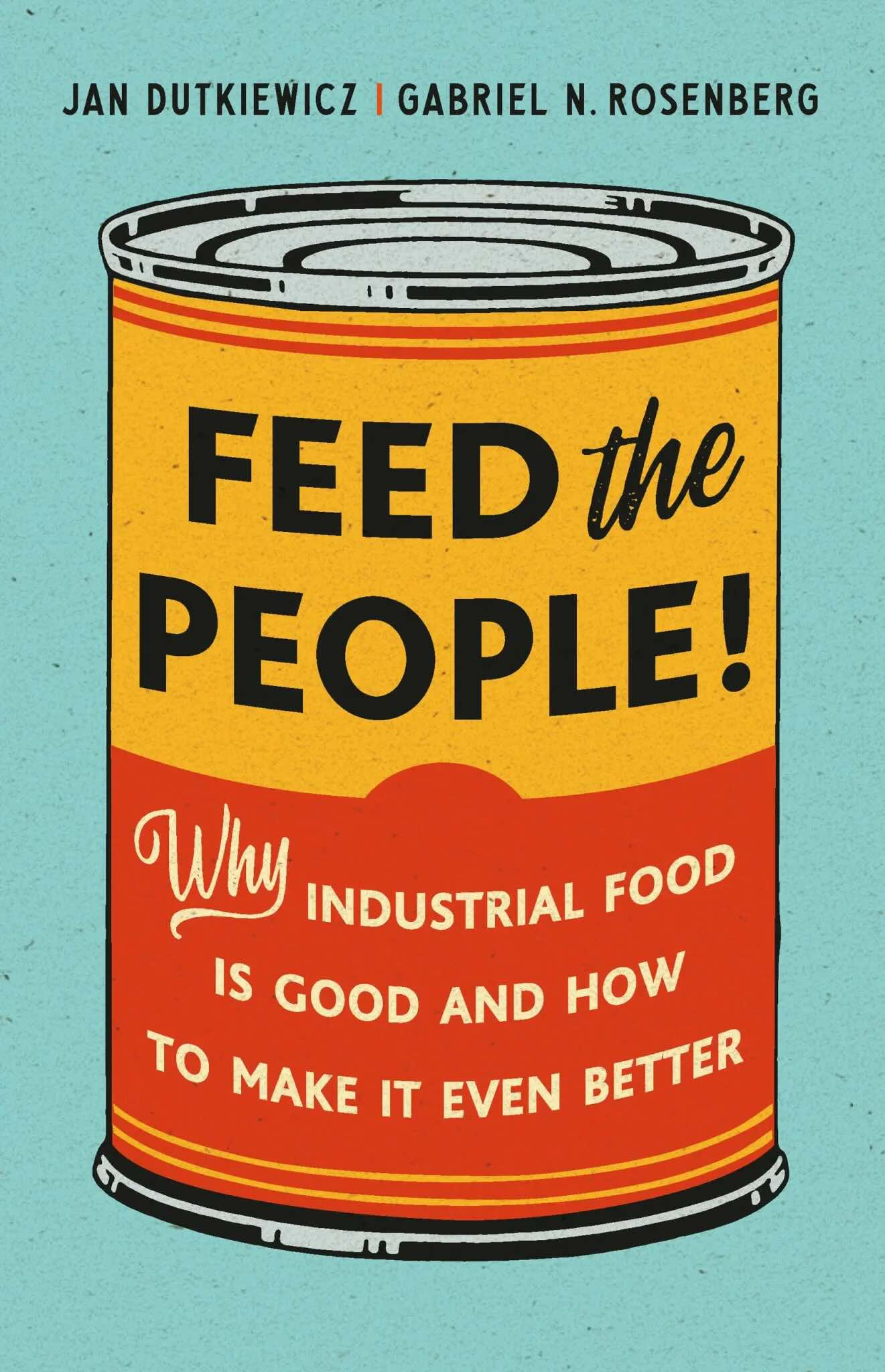

Dear readers, on February 17, my next book, Feed the People!: Why Industrial Food Is Good and How To Make It Even Better, will officially be released and, hot off the presses like cookies from the oven, ready for your eager paws. Feed the People! has been the major focus of my writing energy for the last few years, and I am enormously proud of what my co-author, Jan Dutkiewicz, and I have created. To whet your appetite for the full meal, today I’m sharing the introduction of the book, “The Food System Paradox,” as well as a handy code that, when used on the Basic Books website, will save you 20%. To use it, follow this link, or use the QR code below, and enter FEED20 at checkout. So, without further ado, please enjoy!

Have you eaten at your local Waffle House lately? Anthony Bourdain once remarked that Waffle Houses make some of the best damn waffles around. The waffles at Waffle House are light and crispy, the sugars in the batter caramelized by the griddle to a deep, sweet amber. When drizzled in syrup and topped with a fluffy dollop of butter, a single bite delivers a glorious trifecta of sweet, salty, and creamy. Wash it down with hot coffee in that signature mug. It isn’t the best coffee in the world, but it isn’t the worst, either. And the refills are usually free. Since Waffle House opened in 1955, it has served close to one billion of those waffles.

You might agree with us right away. Yes, you love those waffles. Or maybe they’re a guilty pleasure, a memory you’ve tried to convince yourself that your taste buds have outgrown. Or maybe you’re turning your nose up at the very thought of stepping foot in a Waffle House. But why?

Don’t dismiss these pleasures just because they’re simple and common. Although you might be able to reproduce those waffles on your own with a bit of practice and effort—or maybe you’re the breakfast hero at home, a batter-and-griddle maestro who can outshine them—the reliable pleasures Waffle House delivers are a wonder owed to the scale and precision of the modern food system. And here’s the thing. The waffle you make in your own kitchen? Or that elaborate one with lavender buttercream and black-currant syrup at the trendy brunch spot? Both of those will almost certainly piggyback on the same crops and modern industrial technology as the Waffle House, but the difference is that although you can make a few waffles (and a huge mess) in your own kitchen, and the brunch place can make a few hundred, Waffle Houses turn out on average 145 waffles every minute of every day all year long, and they do it with an inexpensive and dependable consistency that delights the droves of ordinary people who pack their booths 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. That accessibility ensures that you’re likely to see a diverse crowd of people dining there: goth teens hitting vapes and dodging parents, inked-up hipsters heading home from the club, truck drivers taking a break from a long haul, hungry workers between shifts, and families in their Sunday best eating after church. Waffle House is simple, it is magnificent, and its food has been perfected through hundreds of millions of orders.

Waffle Houses are the product of a food system that, for all its warts—of which there are many—manages to democratize and scale access to food and its many pleasures in a way unparalleled in human history. It is a food system of incredible abundance. Of shelves reliably stocked with varied products, food that is safe to eat, and cheap and accessible nutrition for many people. Even if your go-to isn’t a late-night waffle but an early-morning green smoothie, the technologies and systems that make it possible are for the most part the same. In fact, you are more likely to find the raw ingredients for a better future for the food system at the Waffle House than you are at your local farmers’ market.

If the idea that the food system is, for the most part, working strikes you as controversial—or even heretical—you are not alone. An entire food-writing industry exists to convince you otherwise. Much that is written about food today presumes that Waffle Houses, and modern food-production technology and food policy and eating habits more broadly, are the reason, not the solution, for our food ills. Most food writers suggest that the modern food system needs to be discarded and replaced with one where consumers search for locally sourced, labor-intensive, and cooked-from-scratch options, supporting the small, alternative, and artisanal purveyors who represent a pastoral ideal of sustainable food. Inconvenient? Too expensive? Too tired from work to cook for yourself? Quit your whining and do your chores.

But consider that a single Waffle House waffle would be a remarkable achievement in most human societies throughout the ages. The Mesopotamians, Aztecs, Romans, and countless others, though brimming with brilliance, creativity, and ingenuity, did not produce a single waffle. Billions of waffles? An unimaginable achievement in any era other than our own. In premodern Europe, milling flour by hand was time-consuming and difficult labor, usually done by women. Larger mills, powered by water, wind, or animals, were controlled by the wealthy. The finely milled flours needed to produce a delicate and fluffy pastry were expensive and rare, and most people ate coarse and rough loaves when they ate bread. Industrial milling, first powered by steam and then by electricity, made finely milled flours much more widely available, even as improved agricultural productivity dramatically reduced the price of the wheat from which the flour was milled. With the addition of commercial leaveners like baking soda in the twentieth century, the fluffy waffle that had once been the pleasure of only princes is now ubiquitous. And the higher universal standard of living of our time, related in large part to most people not having to work in agriculture, makes those waffles widely affordable and accessible.

Yes, Waffle House has serious problems. It doesn’t pay its workers well enough, its menus are crammed with unhealthy options, and it serves up food that is produced in ways that damage the environment. For some, Waffle House might represent something like the epitome of brokenness: a low-paying, high-fructose, lowbrow, all-monocrop disaster. For these haters, there is no place in the food system for the Waffle House.

But poor worker pay, unhealthy options, and outsize environmental impacts are problems that afflict not just Waffle Houses but most restaurants and supermarkets in the United States, including, often enough, the expensive and artisanal ones. It is precisely these problems that need to be addressed, one by one, to improve our food system rather than abandoning the whole model in favor of nice-sounding but ultimately dubious alternatives.

But doing that means digging into the details of how the food system actually works. Into the environmental impact of the production of different products and what sustainable alternatives exist. Into the relationship between minimum wages and food insecurity for workers, and how they organize for better pay and working conditions. Into some basics of nutrition and food processing, which will tell you that having a few of those waffles now and then is both good for the soul and not all that bad for you. And into which consumer actions and which government policies can help us keep the best parts of the current food system while jettisoning the bad ones.

Our vision for a better food system entails keeping what works and doing away with what doesn’t. So, despite their problems, Waffle Houses inspire us because they offer a vision for food grounded in popular, accessible, and abundant pleasures for all. What people love about Waffle House is also what they love about most of the items served up by the food system as it exists today, in a restaurant or at home, whether it’s burgers and fries, mac and cheese, or a kale salad. We are trained to think of fresh and healthy ingredients as alternatives to what the conventional food system offers, but at scale and at an affordable price point, they are utterly dependent on the same technologies and techniques that make waffles so cheap. The products of the conventional food system are often snobbishly dismissed as the frivolous and empty delights of junk food, but this book shows that nearly all food we eat is the product of the modern “industrial” food system, junk food and healthy food alike. We want to take the best parts of that system and harness them for a broader political transformation.

We come not to bulldoze the Waffle House but to liberate it. The current system directs much of its extraordinary productivity and efficiency into a surplus of profits and delectable treats for a select few players. Let’s change the equation. This book lays out a blueprint for how that same productivity can serve the environment, human and animal health, food access, and labor justice, providing accessible and sustainable pleasures for everyone.

The modern food system presents a bewildering paradox: it’s never been better at feeding humanity, and it’s never exacted a more catastrophic toll. For millennia, most people eked out bare subsistence through grueling agricultural toil. Hunger, malnutrition, and famines were frequent. By contrast, food today is cheap and plentiful. Not only does this allow people to live longer, happier, and healthier lives, but, liberated from the plow, billions of people can enjoy the comforts and amenities of modern life. A world of backyard barbecues, art museums, medical breakthroughs, and, yes, waffles wouldn’t be imaginable without the incredible productivity, abundance, and convenience unlocked by the industrial food system.

Yet the way we eat is also a massive problem. Many components of the modern food system are optimized to put short-term profits above anything else, overworking people, animals, landscapes, and our climate—producing enough food to feed billions while also lining the pockets of corporations and governments. Food and agriculture alone account for nearly one-third of all global greenhouse gas emissions. The demand for crops to feed animals and humans drives deforestation: The world loses ten million hectares of forest every year, an area the size of Kentucky. This drives species to extinction and reduces our planet’s capacity to capture carbon. Food production also sucks aquifers dry while chemical runoff poisons waterways.

The effects on humans aren’t much better. Although modern agriculture produces more than enough protein and calories to feed everyone, these are unevenly distributed. More than 40 million Americans are food insecure. Seventy percent are overweight, 40 percent are obese, and 10 percent have diabetes, driving skyrocketing health-care costs. Meanwhile, the same agricultural expansion that is driving global climate change also supercharges the risk of zoonotic illnesses, with concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) acting as toxic breeding grounds for swine flu, avian flu, and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The people toiling in agriculture are among the most underpaid and mistreated in the economy, and they have some of the highest rates of workplace injury and abuse. The food system is at once the most abundant it’s ever been and, at the same time, is the crisis of our time, an interlocking set of problems that touches nearly everyone.

You may already be familiar with the many problems with how food is produced and consumed. The media are filled with stories of the food system’s failings and the near-ubiquitous statement that “the food system is broken.” Scores of bestselling books, including Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Alice Waters’s We Are What We Eat, and Wendell Berry’s classic The Unsettling of America, have all advanced similar big-picture indictments of how American food is produced and how Americans eat. For the most part, they’ve also converged on a familiar solution: Scrap what we’ve got and start over. Go small, local, and organic to eat your way to a better food system. This approach, sometimes called farm-to-fork, slow food, or locavorism, suggests that consumers can spark broader transformation of the food system by focusing their purchases (and diets) on real food produced the right way, the way it used to be before industrialization and corporatization. They should give up processed junk and eat only whole and fresh ingredients produced through traditional methods on small farms in and around their community and lovingly prepared by artisan chefs and home cooks.

But this approach gets both the past and the future wrong.

A halcyon age of sustainable farming and clean eating never existed. If your great-grandparents were like many people in the United States a century ago, they may well have struggled with food insecurity and serious nutritional deficits. In fact, one of the greatest challenges faced by human societies throughout history has been providing enough food to feed everyone, and when they did avoid famine, even preindustrial societies often used agricultural methods that overtaxed workers and the environment. Although the current food system has many problems, it’s also an improvement for most consumers and eaters over what came before. More importantly, solutions to the problems that do exist—and yes, there are many—must start with a fair assessment of both the current food system’s faults and its benefits. Real, scalable, feasible solutions are right in front of us. We just need to understand what they are and how to make them work

The first step in fixing the food system is getting away from simplistic claims that it is broken. Much food writing and media coverage of food and agriculture is based on this idea, and given the litany of issues we’ve outlined with how we produce and consume food, this might seem like an obvious conclusion. But while we agree that there is much wrong with the food system, “broken” is not the correct word to describe it. And it’s not just the word. It’s a particular way of thinking that leads to that claim. It’s like telling a handyperson your house is broken when the air conditioner is on the fritz and you’re sweating through the couch. It doesn’t convey what components are malfunctioning and for whom this is a problem. In this simple example, fixing the HVAC makes your house comfy and livable again. Saying “my house is broken” won’t get the HVAC up and running, and the claim itself instills a sense of listless dread instead of offering a solution to fix what’s not working. So too does saying that the food system is broken suggest impending peril; it offers no real vision of a better future and only vague gestures at systemic change. We suggest an alternative. To analyze the benefits and failings of the food system—and ask what’s broken and what isn’t—requires grappling with this complexity and engaging in what academics and policymakers aptly call food systems analysis.

To do that, we need to do what most of those who claim that the food system is broken don’t often do, which is explain what exactly the food system is. Not to be too pedantic about it, but the food system is, first and foremost, a system. It’s a network of interconnected but disparate actors and institutions working in concert, but without centralized coordination, to achieve the aim of making food available to consumers.

For the Waffle House to serve up waffles, there is no central Department of Waffle Administration or even all that many people interested in waffles, but rather an entire constellation of different actors who play a part in making sure that all the elements are in place for the waffle to end up on your plate for the few minutes—seconds even—it lasts before you scarf it down. Some of those people—like the truck driver hauling flour down the interstate or the bureaucrat implementing zoning laws for restaurants—may not even know they are in the business of making waffles. It might be tempting to see the food system as a simple process of farmers producing food and retailers and restaurants buying it and then reselling it to eaters, but this would be a gross oversimplification. In fact, the food system is what scholars refer to as a complex system, namely one with relatively simple individual components (seeds, plants, farmers, food companies, commodity brokers, civil servants) but extremely complex overall behavior.

And it is a system that is dynamically interwoven with the other systems that make up our complex society. That’s why, for example, federal government decisions about energy policy determine why so many Midwestern landscapes are dominated by vast cornfields grown for ethanol. And in a capitalist world, a motivating and exacerbating factor for the benefits and ills of the food system is the fact that almost every single actor throughout the food value chain is trying to make a profit. This motivation is often concealed with high-minded rhetoric about feeding the world or looking out for communities or the environment, but any clear-eyed analysis of the food system as it exists must be serious about economic motivations.

There are many ways in which food systems experts have visualized the food system and its constituent parts. Some imagine it as a chain (or a cycle) moving from production through processing, distribution, and consumption (farm to table). Others, like the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, divide up the food system into two blocks, the food supply chain and the consumer-food environment (behind and after the farm gate), and examine how these are affected by environmental and socioeconomic factors. Other models abound, and many have merit. But the one we prefer comes from Nourish, a food education initiative. For our purposes, we’ve simplified the Nourish model a tad to arrive at four subsystems of the food system: biological, economic, political, and social. For a taste of how such analysis works and what it can tell us, let’s get back to that Waffle House waffle.

The main ingredient in Waffle House waffles is wheat. Although wheat is one of the few crops grown in every state in the United States, there are certain climate and environmental conditions that it prefers. This is where the biological system comes in. It includes things like the quality and health of soil, the amount of rain and sunlight available to grow crops over a year, the biodiversity of farming and nonfarming species of plants and animals, and the presence of pollutants (from farming, industry, or urbanization) in a given area. These determine what can be grown, how it can benefit from local conditions, and how it might adversely affect the local environment.

Wheat grows best in loamy soil made up of sand, silt, and clay, and although it requires a steady amount of water to grow from seed to full maturity over about three or four months, it also prefers long hours of sunlight and moderate temperatures between 65° and 75° Fahrenheit. In the United States, this has made Kansas and North Dakota the ideal locations for vast wheat fields, which cover, respectively, 15 percent and 17 percent of these states’ entire territory. And growing vast amounts of it involves monocropping (growing only one crop at a time in large quantities rather than mixing crops), including the use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides that harm bird and mosquito species, and digging wells or diverting water through vast irrigation systems. Increasingly, the limits of such efforts are evident. Much farming on the semiarid Great Plains depends upon water drawn from the Ogallala Aquifer, a vast underground lake that stretches from Nebraska to Texas. All this irrigation means that farmers have been drawing down the aquifer faster than it can be replenished, and many ecologists warn that it will be unable to support large-scale agriculture in the coming decades. As reservoirs like the Ogallala dry up and as soils degrade, the biological subsystem of the food system is now one of its most fragile components.

Paying attention to how biological factors influence the food system underscores a key point: There is little that is “natural” about any food system, and especially not ours. Any food system entails some effort to shape, redirect, contain, and sometimes destroy the biological systems that human societies confront. Nor is “naturalness” something that always makes for a better food system. Foodborne illnesses are perfectly natural, and efforts to limit them involve technology and human intervention, but we humbly suggest that a food system with less botulism is superior. But it’s not just the environmental aspects of food production that are not “natural.” In the market for wheat and waffles, there is little that is natural about supply and demand.

The economic system is the value chain that produces and delivers your food. This is the network of private actors trying to turn a profit or earn a wage from farm to fork. This starts with farmers and farmworkers (an important distinction we’ll get into in a later chapter). But it also includes grocery stores, trucking companies, restaurants, and large food corporations, such as those that produce inputs like fertilizer and machinery like tractors, and also Wall Street traders who buy and sell everything from food commodities and shares in food companies to agricultural land.

In the case of the wheat that winds up in your waffle, the seeds a farmer uses might come from Bayer, the German pharmaceutical company that bought agricultural biotechnology company Monsanto in 2018. Bayer could also sell the farmer the pesticide to be sprayed on the crops. Once it grows, the wheat might be harvested with a John Deere combine. The wheat will then likely be sold to a grain-elevator operator such as Archer-Daniels-Midland Company (ADM) or perhaps a large cooperative like Agtegra. From there the grain will be sold and processed into flour by a flour mill such as C.H. Guenther, which makes all the wheat flour for Waffle House waffles. And those waffles will be cooked on specialty waffle irons made by Wells Manufacturing of Smithville, Tennessee. Meanwhile, the price that farmers are paid or that millers pay elevators depends on a host of factors, including the price of wheat futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which is often determined as much by how good the weather and climate have been during a growing season (there’s that biological subsystem) as by the analyses and sentiments of investors in global markets, such as when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent wheat prices on global markets rising precipitously on fears of shortages.

The point here isn’t just that food value chains are complex and that a wheat seed from Fairmount, North Dakota, will pass through many hands before it becomes a waffle on a plate at 2 a.m. in Decatur, Georgia. Rather, it’s that relationships of power exist within the economic subsystem that have important effects on the food on your plate. Economic actors can, for instance, exert pressure on the political system. By lobbying politicians at all levels of government, including through organized producer checkoff programs like the Kansas Wheat Commission and the Texas Wheat Producers Board or trade groups like the National Restaurant Association (of which Waffle House is a member, and which fiercely opposes increases in the minimum wage) and through direct donations (Waffle House’s biggest political donation in 2022 was to the National Republican Senatorial Committee), economic actors can push for preferential policies and lobby against laws and regulations they see as threatening to their business model.

But the biggest impact of the economic subsystem is actually getting food in front of consumers, into their shopping baskets, and onto their dinner tables. With farmers deciding what they can produce profitably, companies developing new products or new takes on old ones, retailers and restaurants shaping what people can buy with their decisions about stocking shelves and crafting menus, and food companies flooding media and public spaces with advertising (the fast-food industry spends more than $5 billion per year on advertising in the United States alone), the economic actors that make up the food system don’t just feed us; they also directly shape what we eat and, in many instances, what we want to eat.

The profit motive is so obvious you can (and they did) fairly title a documentary Food Inc., but it’s not a complete story because, in countless and often unseen ways, big political decisions shape both corporations and the food they put on our plates. The political system entails all the regulations, laws, taxes, and subsidies that govern food production and consumption. They span the gamut from crop insurance subsidies to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the food stamp program) to expert panels that develop national dietary guidelines. The political system contains all the institutions that push, pull, and mold food production, incentivizing some forms of farming and consumption and disincentivizing others, and it ultimately determines what food ends up on our dinner tables and if that food is safe to eat.

Laws and regulations touch virtually every aspect of Waffle House operations. From the municipal zoning rules for where restaurants can be located to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements in the Food Code designed to minimize the risk of customers getting sick from faulty food storage or preparation, virtually every aspect of our food system is shaped by policy. (This is also the reason that most restaurant kitchens around the country, no matter the cuisine or location or price point, look so similar to each other.) But some regulations, and especially those concerning labor—the line cooks who make those millions of pancakes and the serving staff who deal with hungry, hangry, and outright offensive customers—vary widely from state to state. In Georgia, where Waffle House is based, the state minimum wage doesn’t apply to tipped employees, meaning that a Waffle House line cook might make $7.25 per hour while a waiter or waitress starts at $2.13 and must earn their living through tips, off the goodwill of customers.

But policy and marketing can do only so much. Corporate belly flops like New Coke and the failure of government attempts to get people to eat more fruit and veggies both show that much about what we want to eat is determined by personal taste, context, heritage, and tradition, all of which are shaped by the social system in which we live.

The social system is probably the primary way you interact with food. It shapes what you find delicious, disgusting, and desirable in a meal. The social system is, quite simply, the information, norms, and beliefs about food that are all around you and inform what you want to eat. It comprises the social and information networks, both physical and digital, where we find knowledge, identity, and culture, and that we use to guide our daily choices. It draws from our personal, familial, and national histories, including the stories we tell about what foods are deeply meaningful for us and which ones are just junk or fads. It includes formal education acquired through schools, but also informal information gleaned from TikTok, much of which is hard to distinguish from the many half-truths and lies with which we’re bombarded incessantly through food advertising. The social system also includes many ideas about food that we simply take for granted and that predispose us to believe that our particular foodways are superior. Crucially, this involves ideas about food ethics; about what constitutes good, natural, or “real” food; and about the appropriate ways to change the food system or keep it the same.

Waffle Houses are one variation of a cherished staple of American food culture that sprang into existence during the twentieth century and that is tied to our nation’s similarly distinct love of automobiles: the roadside diner. Usually located at the intersection of major thoroughfares, roadside diners offered food to the growing number of automobile and truck drivers zooming along the dense network of highways crosscutting the US countryside and, notably, built by massive public works campaigns before and after World War II. Because these drivers were usually strangers to the places where they stopped, and in a great hurry to boot, diner menus tended to prioritize simple, affordable, and homey fare that could be cooked (and eaten) quickly and without fuss or pretension. Breakfast staples, such as scrambled eggs, hash browns, bacon, pancakes, and, most importantly, waffles, were a perfect fit, a mass food culture that would appeal equally to someone from North Dakota or North Carolina. It’s simply impossible to imagine Waffle Houses having the same cultural salience in a country where the love of driving vast distances for long stretches was less common than it is in the United States.

Poke someone enough about why they eat what they eat, why they crave what they crave, and chances are that they’ll admit that it is, in the end, somewhat arbitrary. The contingencies of cultural context and personal history play an enormous role, much more so than rational decision-making. This means, in turn, that appealing to rational decision-making to generate better outcomes can take us only so far; people’s deepest desires and assumptions are daunting challenges to even the most carefully crafted and rational schemes to change what they eat. You may not like the Waffle House. You may think the world would be a better place without it. But here’s the dish: No matter how you feel about it, the earnest and powerful love that other people have for the Waffle House is an empirical reality with which you must deal, and one no less powerful than the composition of soil, the price of wheat, or laws setting the minimum wage.

The Waffle House waffle contains multitudes. Each one is a small miracle that requires countless ingredients from across the food system to come together. This is all complicated! And coupled with the scale of agriculture and its myriad impacts, it’s a lot to take in. The food system is an infinitely complex and interesting subject, but it’s also easy to get overwhelmed. Revealing this complexity is the first part of using food system analysis to understand how our food system works. But if all the food systems approach did was show just how complicated everything was, it would not be helpful or an improvement over what you find in most food writing. However, food systems analysis allows three important things.

The first is to show that claiming that the food system is “broken” is nonsensical. To address the benefits and harms of particular aspects of the food system, you need to be specific. The second is to recognize that there are levers to be pulled in many places that can change what we put on our plates. The food system is not one single thing that you choose to take or leave, but rather a series of things open to intervention, change, and improvement. The third is that in working toward a better food future, you can’t start from scratch; you have to start in the here and now. This doesn’t mean that all possible food systems lead to Nestlé, Monsanto, and Waffle House or that ours is the best version of the food system we can hope for. Certainly, all waffles all the time would dull our taste buds and thicken our waistlines. We’re all for options. But thinking more holistically about what exactly goes into a food system reveals that escapist foodie fantasies are a dead end: neither feasible nor scalable nor desirable as the basis for reliably feeding all of society.

And, much like we can’t start from scratch or go back in time to some imagined better age when food and agriculture were great, we can’t pin our hopes for food system change on any one solution. Perhaps even more overused than the claim that the food system is broken are claims that if we just did one particular thing, be it regenerative cattle ranching or eating local or embracing some new technology, we could save the food system or even the world. But the food system is not one broken thing that needs fixing; it is a complex puzzle with myriad options for improvement and rearrangement.

That locavore dream, the small organic farm, fails to address countless aspects of the food system, including treatment of workers and food access for the hungry and food insecure in a country of 330 million people on a planet of more than 8 billion. These are complex questions that can’t be dismissed with a handwave or that will simply disappear if we graze cows on sunny pastures and buy heirloom radishes. We’ll confess that we love fresh produce prepared with care and the odd trip to the farmers’ market. But foodie fantasies have created a smoke screen over viable solutions to the food system’s problem.

The same goes for the Waffle House. We can’t just wave a magic wand at it. For the Waffle House to achieve its delicious promise, it’ll need many fixes, big and small. Increasing the minimum wage would do wonders for many of Waffle House’s workers. Introducing meat alternatives to the menu would make it more sustainable and healthier. Growing wheat that is more resilient to drought using the latest gene-editing technology would protect waffles from price and supply shock in a future altered by climate change. The list goes on. Each problem must be addressed separately, with the understanding that there might be no single solution.

The standard we use for judging solutions in this book is quite simple: They have to actually address the problem, they must have a provably large potential impact on the problem, they must be feasible to be implemented at scale, and their benefits in one part of the food system have to outweigh their potential negative impacts elsewhere. And here’s the kicker: We have all the right ingredients, and the recipe is hiding in plain sight!

Food systems analysis gives us a powerful tool for understanding what’s for dinner, and it can show us where the food system has gone awry, but it cannot tell us, by itself, how we should change the menu. It gives us cooking techniques, but it doesn’t give us a recipe to follow. And recipes for fixing the food system cut to the heart of politics: interests, tastes, values, and beliefs.

And that’s where we turn to a guiding concept of this book and of our vision for a better food system: democratic hedonism. We’ll talk at greater length about this idea in the next chapter, but for now we’ll offer this definition: Democratic hedonism is an approach to politics that sees moral value in the simple pleasures that people experience in their daily lives, and it favors political, collective, and institutional actions to expand access to those pleasures. The goal of this approach is to figure out how to reduce harms and maximize pleasures for as many people as possible. Pleasure, and its promise, is one of the things that defines a good life, and it can motivate and sustain political action, arming people with the fortitude that change requires. When it comes to food, pleasures may be personal and sensual, but they are also frequently social and communal, and, regardless, even solitary pleasures, as food systems analysis shows, are reliant on other people (as well as on plants and animals).

Hedonism alone we find unattractive. Have you ever had the misfortune to sit next to a rich wino at a bar or fancy restaurant? This is a very wealthy person who, not content to wallow in average alcoholism, has transformed their drinking problem into an expensive (and irritating) hobby, drinking only the rarest and most expensive wines, expounding on tasting notes, and paying closer attention to the vintages on offer than to their dining companions. Now consider the Waffle House, where the pleasure is accessible and you’re not going to wax lyrical about the terroir of the syrup. You might, instead, fill up on calories and caffeine for your road trip, laugh with friends, or plot a book about the food system. Let’s shift from the rich wino’s selfish hedonism to the democratic hedonism of the Waffle House.

Democracy is an ethos and system for sharing power and social goods broadly and equitably. From this perspective, pleasure needn’t be a selfish or isolating obsession, a portal to narcissism or self-indulgence. Rather, making sure that everyone has abundant access to pleasure should be a social project that inspires collaboration, care, mutuality, and solidarity.

Put that way, the delicious promise of democratic hedonism aligns with a key concept that scholars use to study food systems: food security. Food security is at the heart of most progressive food politics, from local urban food programs to the United Nations’ global Sustainable Development Goals. A community is food secure if it has regular access to enough safe and healthy food to meet its nutritional standards. In academic terms, food security requires food availability, access, and utilization. Combine these three ingredients with environmental sustainability and labor justice to create our recipe for a better food system. Think of it as a democratically hedonic layer cake.

The first layer of a better food system is availability. Is there enough food produced to meet the nutritional needs of a country, community, family, or individual? In the United States, availability isn’t so much the problem. There’s enough food in the country to feed everyone a few times over. The problem is that what is produced and by whom doesn’t always strengthen food security; to the extent that the food system provides food security, it is often in spite of glaring and obvious problems. Understanding availability means looking at who produces what, where, and why, which also clarifies how and why we might change it.

The second layer is sustainability. Agriculture is one of the biggest users of land and fresh water on the planet, as well as being a major emitter of greenhouse gases. What we produce—how we get food availability—should ideally be as environmentally benign as possible, but that also means changing what food we demand and eat. From farms to food technology to efforts at dietary change, keeping agriculture within planetary limits and minimizing its environmental harms while providing food security ensures not just a more livable planet but also the ability to produce food and provide food security well into the future.

The third layer is access. Can people get the food that’s available? At the most basic level, this depends on whether people can afford the food they need. And if they can’t do it on their own, are there institutions that provide them with food, be it government programs that supplement their incomes or charitable organizations? These questions intersect with more complex ones that are not strictly about food, such as wages, rent prices, and even the physical landscape that people must navigate to obtain food.

The fourth layer is labor. Who are the people bringing food to our plates? How are they treated, and how much are they paid? Most importantly, can they afford to eat, and eat well? This spans the laws, policies, labor disputes, and worker organizing that determine the conditions in which the tens of millions of workers in the food system labor. Those workers are also eaters, which means that attending to their food security requires better pay and working conditions.

The fifth layer is utilization. Once people have availability and access to food, are they eating a nutritious and delectable diet? This is an even broader question. It depends on the quality, safety, and nutritional value of the food itself. But it also depends on whether people are buying nutritious food and cooking it properly. If you’re already at the supermarket and can afford food, but you’re walking right past the produce aisle and bakery to get a Coke and chips, we’re not going to judge you, but that’s a utilization issue. Utilization also raises many of the most rancorous debates in food circles, including about issues like processed food and fast food and about heavy-handed government intervention, such as regulating food supplements and taxing sugary drinks.

The recipe we propose for a better food system is divided into chapters addressing each of the layers above and can be boiled down to this: Food security, done sustainably, while improving the lot of workers will make for a better food system for more people.

Between the two of us, we have been studying the American food system for more than three decades. Gabriel is a historian who teaches at Duke University and writes about the history of agriculture, policy, and science and how all have shaped American culture and landscapes. He grew up in Indiana, and before he was a professor, he worked food services jobs, including as a cook. Now he splits his time between Durham, North Carolina, and Berlin, Germany, where he is a Senior Research Scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. Jan is a political scientist whose research focuses on the environmental, ethical, and public-health dimensions of food production and food policy. He grew up between Warsaw, Poland, and a small village just outside it amid socialist (and then postsocialist) hobby farms before moving first to Canada and then to the United States. Jan is a contributing editor at The New Republic, where he often writes about the politics of food, and is a contributing writer at Vox, for which he has covered food-related issues including the pro-vegan activism of the animal rights group PETA, the science of comparing different foods’ environmental impacts, and the farmer-led protests that shook Europe in 2024. Together, we have written numerous essays about food for The New Republic, Vox, The Guardian, Dissent, and other outlets. Jan is a vegan. Gabriel is not.

Over the six chapters that follow, we will take you on a tour of American food, but maybe not the sort you’re used to. Chapter 1 explains what most American food writing gets wrong, including its weird and off-putting take on food pleasure. It then offers a taste of democratic hedonism as a palate cleanser. This is a chapter of critique and theory offered as a conceptual appetizer. But if you’re eager to bite right into the meat of the matter, you can move right on to the next chapters. Each of these cuts into the layers of that democratically hedonic layer cake. Chapter 2 takes us to farms in Iowa and the nitty-gritty details of the business of agriculture to explain how, why, and by whom most crops are grown in the United States. In Chapter 3 we tackle the uncomfortable topic of how to reduce the environmental impacts of food production, focusing on meat and dairy, foods that are both abundant and harmful pleasures. We find promising low-tech and high-tech solutions being developed in California, the nation’s largest agricultural state. Chapter 4 moves east to New York City and Durham, North Carolina, to look at public programs, from SNAP (food stamps) to school lunches to food banks, which ensure that all people, no matter how poor they may be, have access to a good diet. Chapter 5 follows the thread of economic justice to the South and back to Waffle House, where workers are fighting for better wages and to improve the restaurants where they work. In Chapter 6 we head to Boston to talk about food utilization with nutrition and public health experts, examining some foundational myths and misconceptions about diets, nutrition, and food processing. These misconceptions have important implications for both your personal diet and for how policies and politics can facilitate good health outcomes while respecting personal choices.

At a basic level, the aim of this book is to help you better understand the food system and to arm you with insights about how to navigate it and how it might be improved. Some of the information in this book will be useful to you as you make personal decisions about what to eat; some of it won’t. But even when we can’t help you be a more discerning eater, we think this book will empower you as a citizen. What we choose to eat can be part of an effective politics of food, especially when it is reinforced by collective action, electoral politics, well-crafted laws and regulations, and smart institutional design. We hope that the book teaches you about the opportunities for and challenges of addressing the food system’s many problems and inspires you to get involved in working to fix them.

We want to offer you a different way of thinking about food and its role in our society, one that is responsive to a now-global political crisis in which the basics of democratic pluralism are increasingly called into question. If Americans cannot share meals together, it is hard to imagine that we can live and work together, much less share a national government.

We hope this book inspires your curiosity, not just about where your own food (and food pleasures) come from but also about the way others interact with and enjoy food. Curiosity, we believe, is a prerequisite to the collaboration and solidarity that will be necessary for building a world of abundant, accessible, nutritious food pleasures.