Dear readers, please enjoy this week’s guest issue from, Eleanor Russell. She’s a writer and theorist living in Taos, NM. She earned her doctorate from the Interdisciplinary PhD in Theatre and Drama at Northwestern University in December 2020. Her current book project, tentatively titled The Listening Avant-Garde, theorizes the relationship between mid-twentieth century stand-up comedy audio recordings, sound studies, and the avant-garde. In support of her book, she’s recently launched an excellent Substack, “outside bones,” that you should check out and subscribe to.

If they’re anything like her writing in general, I expect both “outside bones” and The Listening Avant-Garde to be fascinating, provocative, and—goddamnit I’m going to say it—FUNNY. Although we didn’t overlap, Eleanor and I were both enrolled in the same cult small, liberal arts college. Because that cult small liberal arts college is populated almost exclusively by total weirdos, many of the alumni of the cult college, myself and Eleanor included, are part of an online message board—called “plans”—that is so old it was originally run on a VAX network. Eleanor runs a mean plan! It’s in that context that I’ve gotten to know Eleanor and her writing, and come to admire her. She likes jokes. And she writes them well. And perhaps my sense of humor is crude or unsavory, but I think she writes about jokes as well as she writes them: with insight and sometimes a cutting turn that always surprises me.

Today’s issue will agitate some of you. It concerns the humorous stylings of a man you may despise, and your immediate impulse may be to shudder at the notion that one Donald J. Trump is [shudder] funny. But realizing that humor is a central part of Trump’s political charisma is important, not just for understanding Trump and his movement, but for understanding the complicated relationship between humor and politics. Enjoy!

Donald Trump is funny. In fact, it is precisely his ability to be funny that made him a successful politician. In his presidential speeches, in his tweets, in debates, Trump’s authoritarian charisma is most on display when he is facetious and jocular. His performance on the national stage is often a kind of preening silliness, yet unmistakably menacing, and necessarily white and masculine. It is precisely this performance of humor and control, entwined, that makes him dangerous. This is to say that, while there is no short supply of reasons why the Democrats might lose in the coming midterms as well as the next presidential election, I offer yet another: Democrats, and their loyalists, may recognize the fact that Trump changed the national political landscape irrevocably. But that doesn’t mean that they have learned from this transformation—specifically, that Trump triumphed because, not in spite, of his ridiculousness.

It’s July 24, 2017. President Trump makes a speech at the 19th national Boy Scout Jamboree at the Summit Bechtel Reserve in West Virginia. His blaring, smug baritone bounces between topics with the frenetic narcissism of a toddler. At one point, he asks: “But do you remember that incredible night with the maps?” On “maps,” he puts a hand up in front of his face. In the light, his palm is strangely creaseless—again, like a baby. He moves his hand back toward him and then back to front, to the side, improvising his gestures within the fixed coordinates of the space, the lectern, and former Governor of Texas and Secretary of Energy Rick Perry skulking nervously behind him.

“And the Republicans are red, and the Democrats are blue, and that map”—Trump’s hands brace the lectern and his eyes close as he remembers this sensory experience, this fusion of color and glory—“and that map was so red it was unbelievable, and They didn’t know what to say.” Eyes open, crowd cheers. Trump keeps talking. But Perry gets antsy, adjusting his suit jacket, mouth smiling in an image of pride, but with worried eyes behind his knockoff Harry Hamlin glasses.

I find this scene both poetic and comic. Actually, for me, the poetic bleeds into the comic, the merging of sensory categories in stark opposition to Trump’s imagery of an “unbelievable” mass of red. “So red it was unbelievable”—a simile wherein the adjective (“red”) relates to the other adjective (“unbelievable”) but with no substantive clarification or elaboration. “So red it was unbelievable.” Everything about Trump is just so red. Pulsating, alive, but, like Clytemnestra’s carpet, a harbinger of doom. And depravity. But, most of all, I think, dumbness.

It’s likely many Democrats would not find “so red it was unbelievable” to be beautiful, or funny, and even less likely to call it both. By extension, they might not think to call this line either poetic or comic. But, as the scare quotes bely, it is this casual way of defining artistic categories by their greatest successes that is a problem; not all poetry is beautiful, not all poetry is good, not all good things are beautiful, not all things that are beautiful are good. Stated so, this may seem obvious, but it upsets the basic emotional logics of contemporary liberal comedy such that liberals don’t recognize what is probably also obvious to most people: Trump’s connection to his base—and mutual captivation—is deeply and powerfully interwoven with a comedic impulse.

Henri Bergson wrote that laughter is a “social gesture” and, in this capacity, functions as a “corrective.”1 Laughter, he thought, identifies that which is behaving insufficiently human, to alleviate some of the discomfort that comes when we recognize the inescapably mechanical and rote elements of our lives. When Charlie Chaplin falls, we laugh, because falling down means you suck at walking and doing stuff, which is what humans are supposed to do. It also means that, through this comic moment, walking and doing stuff become routine, automatic, and unthought; people walk around and don’t think about the fact that they are walking around and that not everyone can, in fact, walk around or that, sometime soon, they may no longer be able to walk around.2 Laughter, as evidence of the comic, exposes the essential vulnerability of humanity coming from this mechanization; falling down is like when a circuit breaks. Laughter smooths over the rough edges of this realization: the human is insufficiently human.

But in our current moment, with the maps of truth, identity, and belonging being constantly redrawn according to the whims of capital and those who manage its flow, Bergsonian laughter doesn’t identify what is insufficiently human anymore, but rather what is, in the laughing moment, a supplement to the human, an announcement of what the human is now, and an augury of what that new capacity will bear upon the future.3 This is perhaps what Trump’s liberal critics fail to understand about Trump’s comedy, as well as their own. Contemporary liberal comedy is founded on sad smugness, the righteous powerlessness of the faithless. For liberals, laughter serves almost exclusively as a corrective function, a stark reminder that what is shouldn’t be.

Trumpian laughter comes not from correction, or its broken promise. Those in power and the base that love them know that humor can never be wielded against any structure that has, like, drone tech and nukes. To illustrate: some of what happened on January 6 2021 at the Capitol was funny. But the fact that the protestors were capable of humor isn’t why they were able to storm the Capitol in the first place.4

In a sense, Trumpian laughter is the laughter of profane prophecy: “Watch as I turn this gold to shit,” spinning the axiom like a demented Charlotte with a fucked up web. His base’s laughter is the laughter of recognition: the joke is that it’s going to work. Del Close was right. There is truth in comedy.

With the Jamboree speech example, I’m reading into Trump’s language. I’m finding the humor. I’m looking for strange and awful poetry. I’m doing this because his language and comportment invites me to do this. The invitation is clear from how, like a stand-up comic or monologist, Trump engages dialogic modes of address that assumes the audience is already on his side, assumes we are here to learn from him about the way things really are, how things are actually different from what They say they are. “They,” of course, is a floating signifier indicating anyone outside of the redness of that map, the “believable,” as opposed to Trump and his base, who are the “unbelievable” ones despite, they think, in their indignation, actually being in the right!

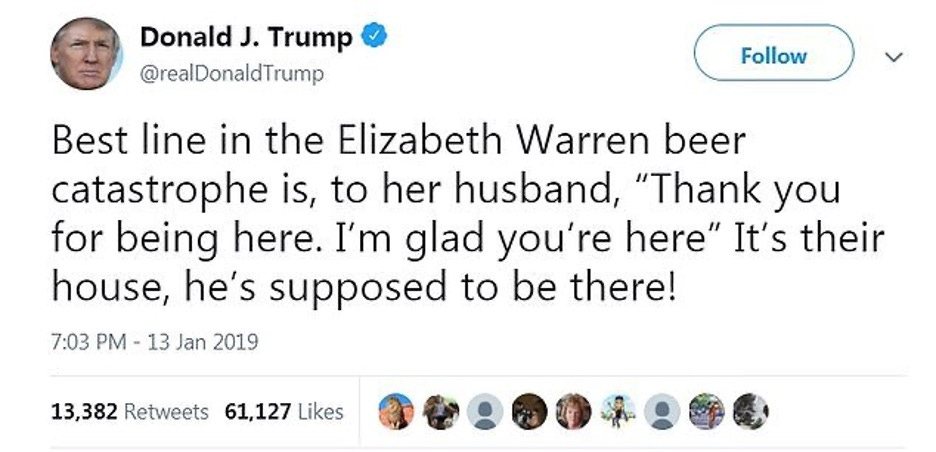

There are plenty of examples of Trump being much more obviously comic than my first example, whether by making an explicitly racist joke, or in a more sardonic way. But as Emily Nussbaum for the New Yorker, Richard Zoglin for the Washington Post, Olivia Cathart for Paste Magazine, and others have noted, for those of us who are not part of Trump’s base, the nature of his humor more generally is baffling to the extent that it does not even always register as humor. For instance, in the tweet thread that spurred this piece, scare-quotes get deployed more than once by self-identified liberals when asked to consider Trump’s rhetoric as a comic object.

“Funny” and “joke” get bracketed by distancing; as such, “funny” and “joke” become aesthetic objects judged as specimens from an outsider viewpoint. Trump’s attempts at humor become subject to analysis, but with the role of physical and sensuous experience elided. But physical and sensuous experience is precisely the domain where humor resides.

On The Late Show on March 4, 2019, Stephen Colbert did a 6 minute monologue covering Trump’s speech at the 2019 CPAC (Conservative Political Action Conference). The speech is extraordinary and, as Colbert mentions, historic: Trump spoke for two hours and two minutes, making it the longest public address by a president in the history of the office. It’s an upsetting, bizarre, funny, feckless, and sinister performance that is worthy of much more scrutiny than, as far as I can tell, it has received.

But Colbert’s commentary is a performance that is practically a masterclass in missing the point. Every line delivery and rhetorical move is a bracketing, an isolation exercise and demarcation of the comic Object (Trump) and the comic Subject (Colbert). Two moments stand out in particular for me:

Colbert shows the clip of the part of the speech where Trump defends a prior incident where, on public television, he asked Russia to hack Hillary Clinton’s email account. In his presidential address, Trump laments the blowback from that incident, whining that liberals can’t take a joke. After airing the clip, Colbert, disgusted, remarks that this defense is absurd. Clearly Trump isn’t joking. Colbert knows what a joke is, and Trump’s initial demand and his ensuing lie are assuredly not jokes, there is nothing joke-like about them. In the clip Colbert is disgusted by, Trump does a bizarre impersonation of himself joking with Russia, and the bizarreness of the performance is what Colbert finds antithetical to comedy: the element of strange surprise.

And:

At the end, when he shows the clip of Trump remarking upon the ridiculous term limits of senators: “These senators, that are there for twenty years—white hair!” Trump mimes a flick of a mane. Slight pause, audience chuckles. “See I don’t have white hair.” Arms spread wide, “what little old me?” style, his face impassive. The audience loves it. Once more to make sure it sinks in: “I don’t HAVE white hair.” Back to Colbert: “You don’t have human hair.” His audience laughs in agreement. End of monologue.

Both these moments reveal a significant cognitive dissonance on the part of the Democratic establishment in the culture wars. Jokes and the laughter they incite, like everything else culturally formative, are dependent upon societal conditions. This doesn’t mean that what makes you laugh doesn’t matter (like Trump seems to think his joke about hacking HRC’s emails doesn’t matter) or that laughter should (or can) be exclusively reserved for jokes advancing ethical or political agendas (like Colbert’s audience, and the people who responded to Gabe’s tweet, might believe in part). Both of these conceptions of comedy are correct in different situations. What Trump’s impersonation of himself telling the truth—that he DID ask Russia to hack HRC’s emails—reveals is that the Trump presidency has exposed the domain of humor as it relates to international politics as a source of power and meaning-making. Comedy is capital, and Trump is spending it. And, as the last couple decades have shown us, the Democrats are more interested in disowning their power as a way to avoid responsibility for their inertia and disloyalty to voters. Liberal comedy illustrates this largely by operating upon this essential contradiction: the comedy of Colbert, Seth Meyers, Trevor Noah,5 Samantha Bee, and others reflect the docile ambivalence of the Democratic Party as an establishment, but, at the same time, this ambivalence is presented as—to risk scare quoting—“speaking truth to power.”

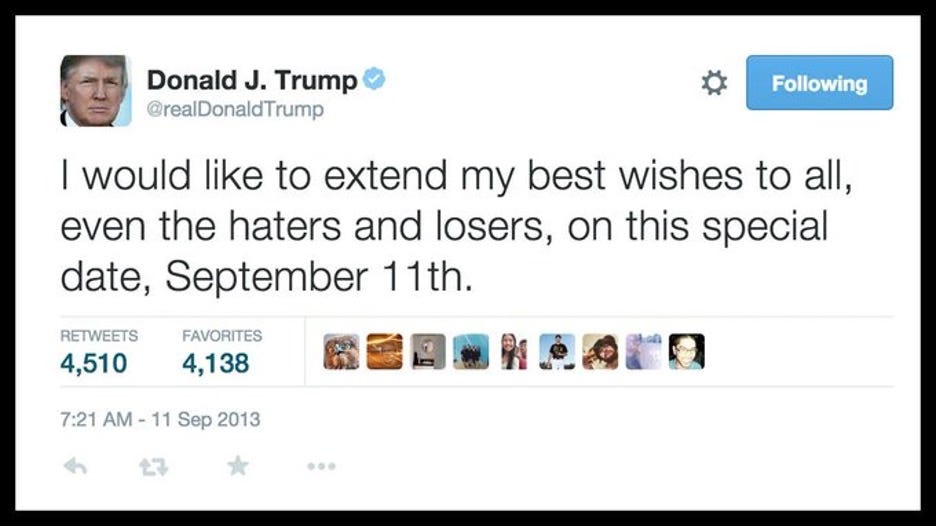

When Trump, backed by his wealth and power and presidential office, says “I don’t have white hair,” I laughed. I laughed because, obviously, Trump has fake hair. But his presidential status and sway over his base makes the obviousness of this fact irrelevant, even, in effect, making the fact no longer true. The word “performative” in popular discourse means “fake” or “posturing,” which is a real shame in times like these because Trump’s rewriting of facts and remapping of reality by the act of telling jokes that he wants to be true is an excellent example of Judith Butler’s (via J.L. Austin) understanding of performativity: ”Within speech act theory, a performative is that discursive practice that enacts or produces that which it names.”6 Through humor, Trump is redefining what facts mean and how they matter in and through the “discursive practice” of joking. The joke tethers a vapid lie to a menacing and very real truth-of-command. Through the joke, the weirdness of Trump’s hair is made meaningless and Colbert’s mockery is preempted such that the joke also becomes prophetic: “You will know the haters and the losers by what they say about my hair, but heed this truth: they are haters and losers.”

In comparison to the self-consciously partisan comic mode of the Democratic establishment in US media culture, Trump’s humor showcases his political presence as a kind of anti-politics. Obviously, in the way that anti-comedy is decidedly a form of comedy, anti-politics is decidedly political. By “anti-politics,” I mean that Trump’s imperative toward the accumulation of capital—financial and cultural—supersedes the concept and formation of “politics” as a fundamentally partisan project. In addition to exposing the fault lines of the Republican Party’s ideological apparatus, revealing who the real future of its base is (we got to know this future better on January 6 2020), and irreparably changing the Party forever, Trump’s election also brought about a crisis of faith in the American experiment for Democrats. As Trump’s success is derived from a fundamental relationship to the comic impulse, so the crisis it brings bears the traces of comic exposure. Upon Trump’s election, the Democrats were forced to at least realize, if not accept, that the ability to augment the truth and to redraw the lines of what truth even means, has been a vital structural principle of US democracy since its inception.

As the litany goes, the Trump regime both created and exposed many ideological contradictions and tribalist divisions between people, voting blocs, institutions, value systems and ethical codes. But humor in the United States—specifically, what counts as humor—remains a special point of tension. Prototypically (neo)liberal conceptions of morality, values, and pleasure are in crisis when someone like Trump becomes a comic subject or object. Specifically, Trump’s status as a comic figure on a national and bipartisan level means that the politics of the experience of humor are at stake. Largely, these politics play out in a sense of speedy immediacy—so different from the turtle pace of both Democrats and Republicans—like a Looney Tunes cartoon: “Covfefe,” for example, plays out as Porky Pig; Trump staring directly into the solar eclipse seems more like the cosmos itself pulling a Bugs Bunny on Elmer Fudd. The political economy of Looney Tunes is bizarre and eclectic. Aesthetically and ideologically, it’s adjacent to surrealism (but Dalí, not Buñuel) and includes a fetish for capital, as Bugs and Daffy, often drawn with dollar signs in their eyes, attest. Trump’s comic authoritarianism is similar to this: loyal only to his own capital, Trump’s humor runs the gamut, with rhetorical and value-vacant discursivity, like a slightly less gleeful Road Runner.

There’s nothing funny about Kate McKinnon dressed as Hillary Clinton playing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” on live television. Because liberal comedy doesn’t have to be funny. You just have to agree with it.

See “Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic,” first published in 1900 (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4352/4352-h/4352-h.htm).

The relationship between comedy, laughter, and physical disability is extremely important for understanding what counts as human and what counts as mechanical; Trump’s repulsive impersonation of a disabled journalist toward the beginning of his campaign has profound implications, I think, for this triangulation, implications that exceed the scope of this piece.

One laughs in recognition of some shared perspectives or in sympathy to failure or weakness in our healthy relationships with friends and families and non-evil performers. That kind of laughter and function didn’t go away. There’s just other modes of laughter and modes of being that we are forced to realize.

The reason they were able to storm the Capitol is because a bunch of them were cops with guns.

Interestingly, in March of 2017 Noah compared Trump's repartee to that of a stand-up comic. It’s worth noting that this observation occurred in Noah’s capacity as an occasional pundit on CNN rather than on his own political comedy show.

Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge (1993), 13.