The Lazy Bear's Guide to Effective Anti-Imperialism

How to Fight the War Machine When Your Head is Stuck in a Jar of Honey

[Above: The Author, a Ph.D. in American History, opines on world affairs. Can you believe I once published something in a journal called Diplomatic History?!]

In this issue of The Strong Paw of Reason, I stumble out of my Americanist cave and opine on matters of global import. Sabres are rattling and there are whispers of war in the East. What’s a humble bear to do?

Today’s newsletter is a return to the long form approach I pursued last year (remember I promised I’d still do that sometimes!). I’ll return to the regular modular approach in the future, but I felt like this essay is substantive enough that it deserved to stand alone. I am not an expert on US foreign relations or international affairs. But I think it’s my responsibility to engage these questions as well as I can with some perspective from my training as a historian.

This issue is addressed to people who don’t like US military actions abroad and want fewer of them. I’m calling that “anti-imperialism” in the title, though I’m aware that doing so sidesteps some important definitional questions that academics may wish to quibble about. If you prefer to describe my skepticism of US military force as something else (“anti-militarist” or “peacenik” or “woefully naive”) feel free to do so, but it doesn’t alter the substance of the argument. And if you happen to be a big fan of US military actions abroad this essay may not be for you. I’m not going to spend much time justifying my peacenik assumptions and hawkish sorts will probably disagree vehemently. Fine. That’s not the point. This essay is for people who don’t like US militarism, want less of it, and, given their limited political agency, hope to pursue an effective anti-imperialism.

To them I say: As long as the United States spends nearly a trillion dollars a year on its massive military, it really doesn’t matter all that much who is in charge; the institutional inertia of the National Security State will always favor war. If you want to contain American imperialism, you need to focus on reducing the institutional capacity to make wars. That’s not an easy task, but knowing that it is the task will help you identify the opportunists and marshal your limited time and energy. Less time and energy spent fighting the war machine is more time and energy spent eating honey!

The United States is a (declining) global hegemon with a world-spanning military apparatus unparalleled in size and destructive force. Its military actions make an enormous difference in the daily lives of millions of people all over the world who aren’t citizens of the United States but whose well-being demands our moral consideration. Those people don’t get a say in how the United States uses its military. Arguably, most average American citizens don’t get much of a say either, but insofar as we have any political influence, no matter how diluted and constrained it may be, it’s our moral responsibility to see that the US uses its military might, if we must use it at all, in a responsible fashion. Great power, great responsibility, yada yada. Ideally, every American citizen would take a serious interest in world affairs. They would learn enough to know when it was good and warranted to use military force and when it was bad and unwarranted. And then they would demand that their elected representatives ensure that military action was reserved only for when it was good and warranted and never when it was bad and unwarranted.

Problem: Americans are lazy and ignorant, and we’re easily hornswoggled by opportunists, fools, charlatans, and the sundry cretins who populate national politics and media.

Many, if not most Americans are shockingly ignorant about anything and everything happening outside of the United States. Charitably put, the world is a big very place and we’re busy and you can’t possibly know everything you need to know so why bother? Less charitably put, we’re a provincial lot with little knowledge of the world and less interest in obtaining it, so we outsource it to pundits and politicos who mostly come in one of only three flavors: cynical, stupid, and cynical and stupid swirl. Now, surely, one could wish none of this was true, and that the American populace would soon become responsibly knowledgeable of, say, the current conflict in Ukraine, but, gentle reader, as my sainted mother is fond to say: shit in one hand, wish in the other, and see which one fills up first.1

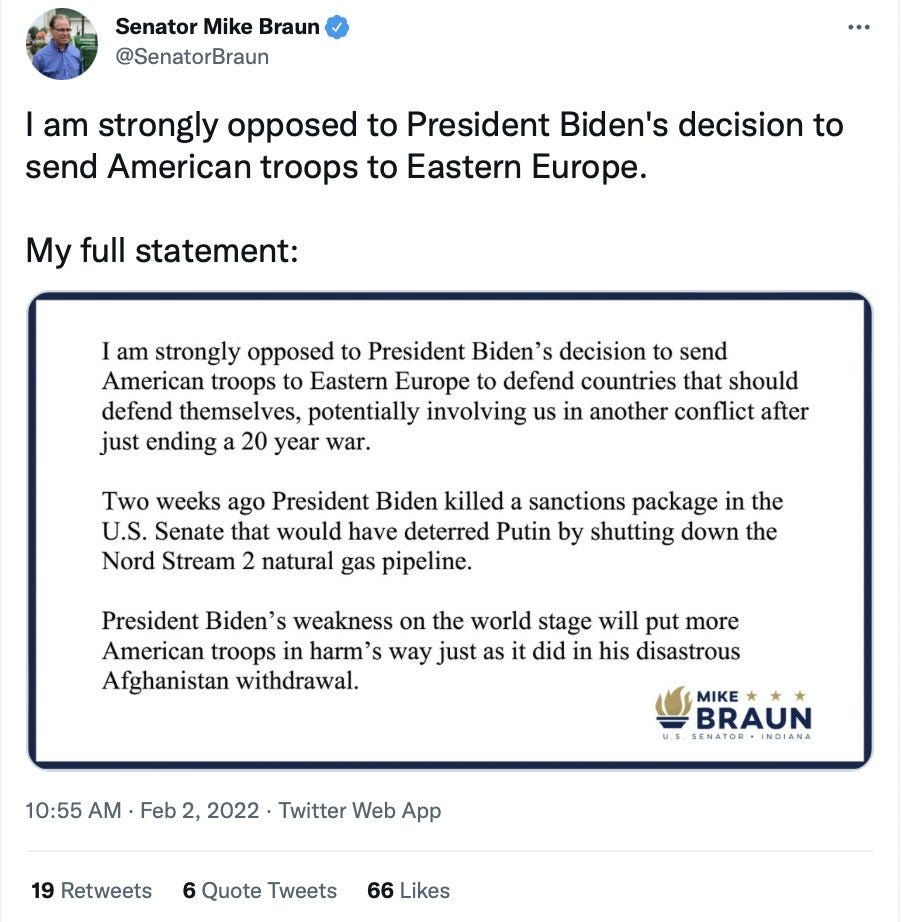

Take this inane statement from an actual sitting US Senator, Mike Braun (R-Indiana), for example. I have low expectations for partisan agitprop, but this is really scraping the bottom of the barrel.

It’s unclear to me if Braun is a fool or an opportunist—probably both!—but the statement attempts to make a right populist argument against the Biden Administration’s decision to deploy several thousand troops to NATO allies, Germany, Poland, and Romania. Braun’s criticism is a muddled, incoherent mess, as Nicholas Grossman helpfully noted, that hinges on both a vague concern about military confrontation and a preoccupation with appearing weak on the world stage. The statement seems to falsely imply that one of two scenarios will befall The Troops: either American soldiers will be placed in “harm’s way” because they will be deployed to Ukraine under threat of Russian invasion or American troops will be placed in “harm’s way” because Russia is going to invade Germany, Poland, and/or Romania. Meanwhile, Braun reverses the conventional arrow of causality by suggesting that a preemptive punitive sanction would “deter” Russia from invading, a notion that is bound to work about as well as a security guard tazing a customer to deter them from shoplifting. Next, Braun suggests that those NATO allies “should defend themselves” and that the US will look weak by defending them, which leads to the cherry on top: Braun dubiously ties this all to Biden’s Afghan withdrawal. No matter how you may feel about that policy, it was an example of Biden removing American military forces from “harm’s way” so that the ally in question would be forced to “defend themselves.” It’s hard to argue that American soldiers would be more in “harm’s way” at a Polish “Fort Trump” than at, say, Bagram Airfield, but, well, that seems to be Braun’s position. All of this prompts important questions: Does Braun want the US military in harm’s way or out of it? Were Trump and Pompeo putting American forces in “harm’s way” and projecting weakness when they agreed to redeploy 5,500 troops from Germany to Poland in 2020? Could Braun kindly stipulate in advance which countries can “defend themselves” and which cannot? Does that list include Taiwan? Or Israel? And just who in his office is responsible for writing this crap anyway?

Braun’s statement illustrates just how easy it is to take the most insipid militarism—endless occupation of Afghanistan!—and rebottle it as nebulous anti-war rhetoric. I agree that military conflict with Russia would be a catastrophe and that the Biden Administration should do whatever it can to prevent that. And I do think you can make a credible case that these deployments are counterproductive or worse. If we go to war with Russia, you can expect me to vocally condemn and to protest against it, as I did during and after the invasion of Iraq. But while Braun may earnestly hope to avoid conflict with Russia at this very moment, I doubt he would, in fact, favor a transformed American foreign policy that reduced US military commitments in Europe, precisely the course of action that would be needed to defuse the larger conflict with Russia. That conflict is rooted in the interest of the US military’s longstanding commitment to the maintenance of operational dominance in a potential European war theater, a commitment, notwithstanding his grousing about whether Romania or whoever was paying their fair share, Trump never seriously compromised. To reduce conflict with Russia in this way would, after all, entail revising our role in NATO in ways that would spell the loss of the tens (or hundreds) of billions of dollars in assets the US military currently holds as infrastructure, bases, and equipment in NATO territories and it would dramatically diminish US military power in Europe and globally. (I don’t see Germany letting us keep Ramstein if we welch on our treaty obligations, for example.) The US military “needs” those assets in those places to maintain its operational supremacy in Europe and because they are vital links in a deadly globe spanning military infrastructure. And if we don’t need operational supremacy in Europe or a deadly globe spanning military infrastructure, why in the hell are we spending hundreds of billions of dollars on defense every year?

My answer, of course, is that we don’t need either of those things and we shouldn’t spend so profligately to maintain them. Braun disagrees. He did vote against the $770 billion Defense Authorization Act in November, but mostly because he’s vowed to vote against all federal spending measures until Trump’s border wall is fully funded and completed. Josh Hawley, meanwhile, voted for the bill, Rick Scott sponsored it, and Mitch McConnell helped Chuck Schumer clear the way in a cloture vote. They all love the war machine, and it strains credulity to think that the US would militarily disentangle itself from Europe, or the rest of the world for that matter, without a dramatic reduction in defense spending that Carlson, Vance, Hawley, Braun, and most other Republicans would name treason. (In fairness, Rand Paul, his many other sins aside, has been a consistent, principled, and vocal proponent of cutting defense spending.)

Because anti-war rhetoric is so easily abused it must be matched by institutional and material commitments you simply won’t find in either political party as they are currently constituted. Of course, the question of when military force is warranted is not a simple one. It’s a moral question, entangled in interpretation, speculation, and clouded by selfish interests. I tend to answer it with strong skepticism of any and all military action, but I wouldn’t defend categorical pacifism. I think, for example, that US entry into World War II was justified, as was decisive federal military action against the treasonous slave power during the Civil War. Pacifism is a fine way to evaluate military action… right up until there’s a good and justified reason for the use of force. When pushed, many pacifists will admit that there probably are conditions under which they would endorse a military response (Nazis! Invading xenocidal lizard people! All of the above!). Practical pacifists and warmongers are not always rhetorically distinguishable: both may well describe military action as a lamentable final course of action prompted by exceptional danger. Given this, how can we ensure that military force is, in fact, the exceptional course of action?

My recommendation is to concretize skepticism of militarism in institutional arrangements, to bend institutional defaults away from militarism such that war-making capacities must be fabricated before they can be deployed and are starkly limited in duration. In simpler terms, it should be politically, socially, and logistically difficult for politicians to prosecute a war and we should organize government agencies, including budgets, to reflect this fact. That’s a good reason not to deploy troops to Ukraine, but it’s also a good reason not to fund the military as we do.

This is, to a great extent, a practical lesson I take from the history of the two military engagements I named above as justifiable. Both the Civil War and World War II were watershed moments in the construction of American state capacity. In both cases, the Federal government was faced with such a pressing military danger that it had to whip up popular support for military action and constitute a fighting force. That entailed dramatic and unpopular disruptions of daily life in which average citizens were expected to subordinate their own interests to those of the state and war effort. And it required the creation of vast new state bureaucracies and unprecedented interventions in the national economy. And it also involved important and persistent constitutional reorderings that fundamentally altered the shape of how lawmaking, courts, and ordered liberty functioned. In the case of the Civil War, many of those constitutional and governmental reorganizations were ended in a premature fashion, leading to the failure of Reconstruction. But in the case of World War II, the United States never really wound down what historian James T. Sparrow terms “the warfare state,” instead rolling it into, first, the Cold War State and, now, the National Security State. I think that was a grievous error precisely because it has allowed 80 years of conniving and opportunistic politicians to free-ride on the necessary national mobilization executed by Roosevelt. We no longer need to reorganize American society to prosecute a war; we often need to reorganize it just to prevent a war. We have made it easy for politicians and generals to start wars because the unchecked institutional default is to lavish improbable sums of money on the military and defense contractors and to stock their bases with missiles and jets just waiting to be used. (Not that the jets always work.) Even when we don’t have a hot conflict going, our war machine is the Chekov’s gun of American political theater.

This institutional context makes so much anti-war rhetoric, my own included, fine words scolding the storm. This rhetoric is too easily appropriated by warmongers and deployed as a partisan cudgel to criticize the party in power, only to see the ascendant party make use of the same military apparatus when it has taken control. This was (and remains) a regular criticism of the Obama Administration in some quarters. If you’ll recall, Obama had campaigned as a credible critic of the disastrous invasion of Iraq. Along with a majority of the Democratic Senate caucus, Hilary Clinton had voted in favor of the Authorization of Military Force Resolution (2002), while Obama, still a state senator at the time, had not. I wouldn’t exactly call Obama’s rhetoric dovish, but it inspired some (imho unwarranted) optimism among Democratic voters as well as some vitriolic criticism from the Right. Depending on how much hope one invested in Obama’s foreign policy, the succeeding eight years were possibly disappointing, with the Obama Administration sustaining an open-ended military presence in Afghanistan and asserting the right to engage in drone strikes, bombings, and targeted assassinations whenever they felt national security required it. If one believes the Glenn Greenwalds of the world, Obama’s foreign policy and commitment to the national security state was a seamless extension of Bush II’s and most Democratic media types were all too willing to forget about US militarism once their own guy was in the White House. Greenwald now also makes the same criticism of the Biden Administration and the current Democratic party. One needn’t agree entirely with Greenwald’s assessment—you may justifiably prefer Obama’s foreign policy to Bush’s and Biden’s to Trump’s on the particulars—to, nevertheless, recognize that, however Obama and Biden deploy the American war machine, both are unflinching about maintaining America’s capacity to unleash massive amounts of violence on the rest of the world.

Neither Obama nor Biden are unusual in this regard. Senator Bernie Sanders has long been sneeringly dismissed in national media as a loony leftist, despite his persistent national popularity, because he has been a stalwart critic of defense spending. He has been politically isolated and marginalized for his longstanding commitment to reducing America’s capacity to make war. But maintaining such a capacity, at extraordinary expense in lives, liberties, and lucre, has been a near constant in American political life since World War II. Recent military actions as part of the “War on Terror” have cost the US $9 trillion and killed more than 900,000 people in the last two decades alone. But the National Security State remains the ideological and institutional container within which partisan disagreements play out and that has been so, at least within the narrow band of respectable national politics, for the past 80 years without serious interruption. People may disagree with how to deploy the American war machine. Some even believe—earnestly and resolutely—that America should rarely deploy it and is or has been badly misguided in deploying it in the past. The arguments in polite political society, however, remain focused on the when of deployment—”now? no!”—and rarely pose the more fundamental question: should the United States maintain a war machine at all? That’s a shame. Just as the most effective deterrent to driving a Lamborghini is to not have a Lamborghini in your garage, the most effective deterrent to US militarism would be for the United States not to have a war machine.

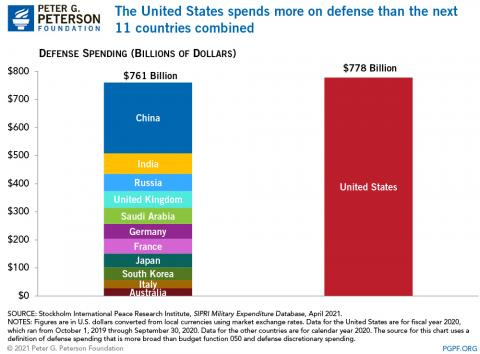

And what a war machine it is! The amount of money the US government has invested in its military is truly mind-boggling. It is beyond counting. No really. Pentagon spending has never been audited. Current Department of Defense annual discretionary expenditures are $770 billion, but a fuller tabulation, including things like the Homeland Security, Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Energy’s contributions to the nuclear arsenal, could put the total annual tab at nearly $1.2 trillion conservatively estimated. It is true, as hawks are fond to note, that current spending on defense is lower than it has been for most of the past century when taken as a percentage of GDP. And it’s also true that the US spends a smaller portion of its GDP on its military than do Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Russia. Yes, that’s all true… and an unpersuasive rationale for current spending levels! The US has the largest economy in the world. The US economy is 14 times larger than Russia’s and almost 50 times the size of Israel’s. You don’t fight wars as a percentage of GDP. It’s the absolute size of your military that matters and the US war machine towers over everyone else. When we move past the percentage of GDP smudge, you’ll notice that Russia spends only about $60 billion annually on its military, a mere 5% (!!!) of the $1.2 trillion total US tab I mentioned above. And even that understates the relative difference in size since decades of capital investments in military infrastructure and equipment compose the unrivaled total assets of the US military. Sure, the military is a huge sinkhole of waste and fraud, but it also owns a bunch of stuff! The (unaudited) Department of Defense’s own (probably low-balled) accounting suggests it holds $3.2 trillion in total assets, a sum that is only about 50 times as large as Russia’s annual military expenditures.

Given this context, my own sense is that critiques of US military actions are too concerned with the ideological rationales for particular actions, and not concerned enough with institutional design and material interests that mobilize them. I doubt very much that we are likely to radically alter the guiding ideology of America’s political leadership—there’s a longer post on this yet to come but even Trumpkins are the weird, spoiled fruit of liberalism—but even if we did, institutional inertia alone could still overdetermine a casually fatal militarism. Transaction costs are an important deterrent to action—perhaps the most important deterrent from an institutional perspective—and 80 years of defense spending has helped to radically reduce the transaction costs of military action. Indeed, in the case of the invasion of Iraq, some portion of our political leadership was captured by a sunk cost fallacy: We’d already spent trillions on the war machine, so why not put it to some use and, in Jonah Goldberg’s shameful and abhorrent quote of Michael Ledeen, “pick up some small crappy little country and throw it against the wall, just to show the world we mean business.” Because, why not? What’s the worst that could happen? The institutional gravity of a $3.2 trillion dollar war machine is such that if you keep one in your garage, the particular reasons to use it will find you.

Knowing that Iraq and the global War on Terror were very bad wars only gets us so far since it seems inevitable that, at some point, politicians and voters both will be enthusiastic about other bad wars. And how will we stop those? As I have already stipulated, the fine-tuned adjudication of the rights and wrongs of future military actions requires a level of expertise that is currently unavailable to most American citizens. I agree with folks such as Daniel Bessner and Stephen Wertheim that a huge part of the problem is that average American citizens are excluded from influencing American foreign policy and that to turn away from endless war we need to effectively “democratize” that debate. We can lament the fact that the average American is both ignorant about world affairs and, at once, profoundly alienated from participating in debates about foreign policy. But it remains the reality, the good work of the Quincy Institute notwithstanding. In the meantime, that adjudication, rarely fine-tuned in national media discourse, is run through with bad faith actors who are interested in advancing their partisan interests, lack a sincere desire to reduce US military action abroad, and may convert political capital accrued through such criticisms into advancing the interests of that military apparatus in the near future. Similarly, my gloss is that the removal of voters and citizens from foreign policy decision making is part and parcel of the redesign of the American state during World War II. In this sense, allowing citizens to shape foreign policy would require not just a change in attitudes by both elites and average citizens, but, in a deeper sense, it would require a broader reorganization of the American state, its boundaries and objectives, and the interests and constituencies it serves. There’s some reason to be optimistic that such a reorganization would be broadly popular with American voters. But, as of yet, there is simply little institutional support for dramatic military spending cuts from within either major political party. The centrist and wonkish wings of the Democratic party don’t yet seem to recognize anti-militarism as a potential component of a “popularist” agenda, despite the popularity of cutting defense spending. But absent an effort to meaningfully reduce that spending, arguments about military action—which ones to support and which ones to denounce—are destined to be chafe in America’s own spiraling Forever Culture War, based less on a serious reflection on the catastrophic touch of American power and more on a gestural affinity for your team’s current imperial enthusiasms.

Effective anti-imperialism will radically reduce the size of the American military or it will do nothing. And anyone who fails to endorse such an approach is unserious about how to temper the military violence American unleashes on the world. Those statements lays out the monumental nature of the task in no uncertain terms, and I hope their clarity offers you something of value. At the very least, it gives you a ready-at-hand instrument to distinguish the opportunistic criticisms of the Hawleys, Carlsons, and Vances, on the one hand, from the difficult political commitments that, on the other hand, would effectively reduce militarism in the longer term. This is a distinction that seems increasingly lost on Glenn Greenwald, but it remains critical to articulating an effective anti-imperial politics.

It’s so simple that even a foolish bear can do it. Whether your head be stuck in a jar of honey or some other crevice, you need only ask this question: Does the person criticizing US defense policy support drastically reducing the size of the US defense budget? If they don’t, they’re a bullshitter. They’re not looking to rid the world of the US war machine. They just want to be the one to drive it.

My mother has never said this.