I’m writing this now on Thursday morning, but I started writing this post before the events of Wednesday transpired. It was a disturbing spectacle. This was for the straightforward reason that the President was, once again, openly trying to disqualify the votes of more than half of the electorate, undeterred by large portions of his party and now propelled by a lawless crowd of Qanon enthusiasts and Neo-nazis rummaging through Nancy Pelosi’s desk. But it was also disturbing because the band of insurrectionists ransacking the Capitol, so visibly farcical and pathetic, swamped the police that were supposed to stop them. (Apparently now we learn this may have been by design). My sister, who lives in DC, texted me to say that while it was horrifying, if you could distance yourself from that horror, it was also blisteringly funny, like something from a zany farce. She was right! (She usually is.) She also perfectly predicted what would transpire. Within hours Congresscritters were back to making their speeches, puffing up about America as the city on the hill, “getting back to work,” and making sure we set a good example for all the little baby democracies out there that are still learning not to let angry mobs trash their seats of government. (“Set a good example for the children!” Lee Edelman please contact your office).

Our Congresscritters were not just undeterred by the mob in the sense that they would continue the certification; they were also resolute about not learning anything new about the not-quite-as-exceptional-as-we’d-like-to-believe character of American democracy. It was as if our governmental order was a character in the aforementioned zany farce, who having been pied and pantsed, was now trying to give the camera a stentorian lecture, all while banana cream dripped from his face and with his trousers still around his ankles. Who was this clown they called American democracy? It would have been better for democracy to die in darkness; at least then no one would see this humiliation.

The thing is this: democracy, for better or worse, didn’t die. It thankfully continues. They certified Biden. He will be inaugurated. The danger—and it is quite serious—is not that Trump will cling to power, but that the American political order will try to reconsolidate yesterday as if nothing happened. I think one way to avoid this is to confront the ugly and sad nature of what Trump is and what he is likely to become when he is no longer president. Trump is positioned to become something we have literally never seen in an ex-President: what I’m calling a party despot and, specifically, the GOP’s despot. By despot I mean something specific and technical, but the thing I want to stress is that despots, as a type, have certain strengths and certain weaknesses. We’ll come back to this in a bit.

I. Before the Mob

I want to start with what happened on Tuesday, before yesterday’s mess. On November 10, I tweeted that I thought that Trump’s whining about vote-rigging was going to transform the Georgia Senate run-offs from easy layups to contested jumpers: The GOP might still score, but Trump was going to make it much harder than it needed to be.

My thinking on Georgia went like this: while a narrow majority of Georgians had just rejected Trump, the same electorate had favored Perdue (and maybe Loeffler depending on how you interpreted the vote). If you added the weight of incumbency and the basic electoral advantages statewide Republican candidates have enjoyed in Georgia since party realignment ran its course two decades ago (Remember Zell Miller?!), these should have been easy GOP holds.

But Trump’s hissy fit was nationalizing the race and making it about vote-rigging. For anyone who hadn’t voted for Trump in November, Trump was saying their votes should effectively be tossed out. Republicans have demonstrated in the recent past that there are political advantages to disenfranchising your opponents, but the smart way to do it is to conceal your intention to do so until after you’ve won and are in position to implement your will. And that was the basic problem: despite what he may have believed, Trump didn’t win in November. Transforming the race into a second referendum on his presidency—this time with some funky conspiratorial flavors in the mix—after he had just lost the first referendum seemed, well, like a clearly flawed plan. Moreover, Stacey Abrams and the Georgia Democratic party are proving to be very effective politicians, reliably mobilizing black voters and the white, college educated suburban voters Trump has been hemorrhaging. An excellent way to make Abrams’ job easier was for Trump to implicitly argue for disenfranchising Georgia’s black voters, who have a very good, historically concrete reason to be extremely vigilant about the threat of political disenfranchisement.

Whatever upside there was to agitating the Trumpkin base through grievances about vote-rigging, there were equal (and I reckoned probably greater) downsides to mobilizing a huge black turnout and depressing some of the GOP vote by attacking GOP elected officials and spreading wild conspiratorial takes. Neither downside risks needed to be dramatic—November’s vote was so close that even a small surge in black turnout and a slight attrition for GOP voters would lead to a Democratic victory. This is basically what happened. Black turnout surged. And there was a modest relative attrition in some GOP counties. Voila! Narrow victories for both Democratic candidates.

There’s undoubtedly more to be said about the Stacey Abrams’s brilliance as a political organizer and the ideological and policy content of the races. (For example, I think the $2,000 stimulus check was important, and I think it’s also significant that Warnock out-performed Ossoff, despite running to the left of him.) But, for now, the thing I want to focus on at the moment is the flip-side of Abrams’s mastery of retail politics and organizing: the infrastructural weakness of the Trumpkin GOP and how Trump is positioning himself to be the GOP’s despot. What I mean by this is that Trump wields unparalleled despotic power within the Republican party but he has very weak infrastructural power. Moreover, while Trump’s despotic power will live on when he is no longer President, virtually all of his extant infrastructural power, weak as it is, was tied to his office and will rapidly decline in its absence.

II. What is Infrastructural Power?

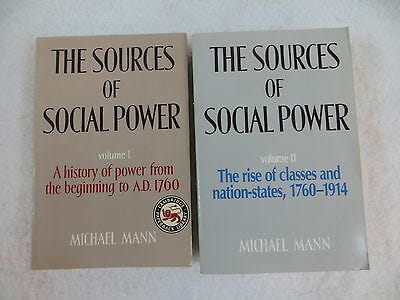

What do these terms mean? I draw the useful distinction between despotic and infrastructural power from the UCLA historical sociologist Michael Mann. Mann famously (to historical sociologists!) elaborated this distinction over thousands of pages spread across four volumes called The Sources of Social Power. This mammoth work endeavored to give a history of power from human pre-history to the present (seriously!), in case you’ve been worried your career goals weren’t ambitious enough. If you don’t want to read all four or five thousand pages, I recommend this essay he wrote in 1984 that offers a concise summary of the theory behind it.

Despotic power is the formal prerogative enjoyed by the sovereign to do stuff. A ruler who has “high” despotic power, for example, can issue decrees without needing to get them counter-signed by Parliament. They can put you to death on a whim, without a trial or even a crime. They may even may claim universal jurisdiction, such that (on paper) they can impose their will anywhere, anytime without limit. This ruler can, in theory, do whatever they want—like a despot!

As Mann observed, it’s one thing to say you’re a despot, but it’s quite another to actually implement your despotic will. Say there’s a King—we’ll call him King Gabe of Bearland—and there’s a rich aristocrat—let’s call them Duke Vance. On paper, King Gabe has very robust despotic power. The constitution of Bearland gives him the right to do whatever he wants, including dictating that people who irritate him have to wear unattractive shirts that are several sizes too large. Duke Vance irritates King Gabe and so, in keeping with his powers, King Gabe orders Duke Vance to wear an overly large unattractive shirt. Where’s the hitch? King Gabe lives in the palace, but Duke Vance lives in a remote manor. Duke Vance says he’ll wear the shirt, but he says it in a way that makes King Gabe think he’s being sarcastic. And King Gabe hears rumors that Duke Vance isn’t wearing the shirt, but since Duke Vance is all the way out there in his remote manor, it’s hard to be sure. King Gabe could march his palace guard to the manor, but what then? Assuming he can defeat Duke Vance’s forces, does he want to execute Duke Vance? But if he executes Duke Vance, King Gabe actually doesn’t get what he wants: Duke Vance isn’t wearing the funny shirt if he’s dead!

What King Gabe needs is the ability to check from a distance on the status of Duke Vance’s shirt and to come up with a set of intermediate incentives—penalties and enticements—that will encourage Duke Vance to do King Gabe’s bidding without the need for violence. An King Gabe will need the ability to verify that his bidding is actually being done. King Gabe needs a spy network or, at least, a Bureau of Shirt-Wearing Compliance, and, in addition, he needs tax revenues to pay his spies and/or shirt-compliance inspectors. But King Gabe doesn’t have those things. All he has is the formal right to tell Duke Vance what to do, but he lacks the logistical capacity to logistically implement his will. In Mann’s terms, King Gabe has plenty of despotic power but not enough infrastructural power—precisely that logistical ability to implement his will.

(At this point, some readers will notice some important parallels between Mann’s thinking and Michel Foucault’s distinction between disciplinary and sovereign power. For some complicated reasons I don’t want to write about today, Mann and Foucault are not identical, but they can be made to be complementary. If this is the sort of thing that interests you, I recommend the work of another historical sociologist, Philip Gorski, and, in particular, his essay in this volume.)

Back to Trump! Mann developed these terms for states, but I actually think they have value for analyzing other kinds of political organizations, such as political parties, and I want to think about Trump’s GOP in these terms.

III. Your Own Personal Despot

One of the signal features of the Georgia story I’ve told above is that Trump is personally lazy, undisciplined, mercurial, and unpredictable. While he expects GOP politicians to do what he wants, he isn’t good at making clear what he wants beyond the vague directive to follow his orders. But, again, it’s hard to know what he wants them to do! His orders are unclear, poorly communicated, and frequently contradictory.

Take, for example, the $2,000 stimulus check. There were plausible arguments that the GOP would be well served by a larger stimulus check. There were also plausible arguments that they would not be well served. What did Trump think? No one knew! He was too distracted by the vote-rigging stuff and had entrusted Mnuchin to represent the White House in the negotiations. Those negotiations resulted in a $600 payment, which everyone thought was fine with Trump, which is why Loeffler and Perdue both voted for the bill. But then… surprise: It turned out that that was not what Trump wanted! So Perdue and Loeffler should campaign against the bill they had voted for? Which they did? But then the Democrats saw an obvious opening and made it clear that it was Mitch McConnell who was stopping the larger check, which, in turn, created the awkward scenario where Perdue and Loeffler were arguing they needed votes so they could support McConnell, precisely the person who was holding up the larger check that had now, thanks to Trump, become the hottest issue of the day outside of vote rigging. Mix in the veto override, which Perdue and Loeffler neither voted for nor against, and you have the sense that Perdue and Loeffler desperately wanted to do the President’s bidding, but they couldn’t figure out what he wanted them to do. The result was a huge nonsensical mess that garnered not the slightest electoral advantage for the GOP and also didn’t change the outcome of the underlying policy dispute.

That’s microcosm for Trump’s poisonous role in the Georgia runoffs. I don’t mean this in the sense that Trump’s legislative agenda or ideology are unpopular in Georgia and therefore his imprimatur is worthless. After all, it’s hard for a legislative agenda to be unpopular if it doesn’t exist and Trump’s most cogent ideological commitments—a gooey mix of white supremacy and chauvinistic nationalism—are popular in large parts of the United States and Georgia. I mean that Trump was poisonous by the more banal standard of retail politics: he kept interfering with the ability of the Republican party to articulate a coherent message and to run a successful campaign. This is because he didn’t actually care about the fate of Loeffler and Perdue or the GOP’s senate majority. In the past 48 hours, we’ve learned that he didn’t want to go back to Georgia to campaign again and that he also wasn’t bothered that they lost because they hadn’t backed his vote-rigging nonsense “enough.”

The problem Republicans must by now realize is that much of what makes Trump a magnetic figure at the bully pulpit, makes him unusually ineffective as a party boss. He’s narcissistic. He’s lazy. He’s ignorant. He’s selfish. He’s cheap. Because he doesn’t know anything about how government operates and is too lazy to learn, he has wildly unrealistic expectations about what any particular person can accomplish. And while he demands absolute loyalty from everyone else, he isn’t bound by even the slightest bond of reciprocity. These are all problems you can manage by ignoring his tweets, sitting him in front of a TV playing Fox News, and occasionally coaxing him to sign tax cuts, but it becomes a real problem if you need him to anything more complicated or sustained. Trump is—and always has been—a compelling and hilarious media personage; that’s how he made his money. He has never had the discipline, smarts, or desire to effectively run an organization.

But running a party is hard work and it requires both pragmatism and sometimes sacrifices. Mitch McConnell is an epic grinder, and like a smart party boss he understands the value of knowledge, reciprocity, and incentives, the relational interstices of infrastructural politics. He gathers information about how many votes he needs and where his caucus is. He dispatches his whips to coax, threaten, and cajole. And he issues hall passes: he knows when he doesn’t need someone’s vote and letting them walk away will save them a headache in the next election. He trades those hall-passes for future concessions. Because Senators are powerful and hard to dislodge—they wield quite a bit more autonomous power relative to members of the house—all of these are necessary to maintain his control over the chamber. McConnell also arguably has a fairly narrow legislative agenda—he wants to cut taxes and confirm GOP judges—but he has been ruthlessly effective at pursuing it.

National political parties are, in some respects, more complicated to manage than the United States Senate and, in other respects, less complicated. They’re vastly larger and they have to operate in thousands of jurisdictions with different rules about how to organize political power. (The operational rules of the North Carolina GOP are not identical to the operational rules of the Indiana GOP.) But they’re also far more amenable to hierarchical, verticalized power relations: the state party chairman, for example, wields formal power over their party in ways that the Senate majority leader does not control his senate colleagues.

A tight, well-oiled party organization is certainly possible and, if you can set one up, you can amass quite a bit of power. Stacey Abrams shows that, but so too does the GOP’s extraordinarily successful 2010 state legislative gerrymandering initiative. They strategically targeted state house races around the country to flip control of those state houses in anticipation of the decennial redistricting. It required incredible levels of planning, information gathering, tradeoffs, sacrifices, and discipline. And it is perfectly unfathomable that today’s Trumpkin party could pull it off like the pre-Trump GOP did in 2010. As New York Democrats will tell you, if your party is poorly organized, you get chaos, defections, gridlock, and the inability to press your formal advantages. This is because the sorts of people who work in politics are mostly ruthlessly ambitious cynics who are servile when you have them under their thumb and viciously retributive when you don’t. They’re also quite clever, which means if the party boss cuts them too much slack, they will interpret their orders to serve themselves and not the party boss. You have to watch them closely, keep tabs on them, and discipline the hell out of them.

You can probably see what I’m driving at here: what makes Trump a lousy President will also make him an ineffective party boss. Because he is extremely popular with the party’s base, you can expect that politicians hoping to succeed in GOP primaries will have to pay him respect and, perhaps, some sort of material bribe. But does Trump care about who would be the most effective candidate for Georgia Governor? Does he have the ability to gather the relevant information to do so? Does he have the discipline to support a marginally less servile toady who would be more likely to beat Stacey Abrams in the general election? The answer to all these question is: No! Trump doesn’t care. He doesn’t know. And he’s too vain to let those considerations steer his thinking regardless.

Added to all of this is the fact that what infrastructural power Trump does wield is largely an artifact of the publicly-financed staff he employs, a few of whom, one imagines, are effective and ruthless operators. Will Trump pay for that large staff out of his own pocket? He’s cheap! But what about the millions in donations he’s been raking into his new PACs, you ask? Trump’s well-documented business MO before becoming President was to use the cachet of his name to get people to give him money for various real estate projects. He then would stiff the contractors and run off with as much as he could carry. When people finally stopped giving him money, he became a reality television show host. The Trump “Organization,” such as it was, was not actually very large in terms of personnel, and its number one business was promoting Donald Trump, not building stuff (which, you won’t be surprised to learn, requires lots of infrastructure!). The idea that Trump is going to spend all those millions to build some sort of effective political machine to meddle in races he doesn’t care about or push for policies he, again, doesn’t care about? Call me a skeptic!

Trump is going to be the GOP’s boss. But he’s going to be a despotic boss. Lots of symbolics of power; no capacity to actually implement his will. All despot. No infrastructure.

IV. The Despot and the Mob

This brings us back to yesterday. Popular despots can, of course, effectively direct disorganized political violence. To return to King Gabe, if he were popular, he could direct the citizens of Bearland to rise up, storm Duke Vance’s manor, and make him wear the damned shirt. There have been rulers who compensated for a lack of infrastructural power through a combination of personal popularity and a willingness to ruthlessly apply violence when and where they could—let’s call it the Richard the Lion-Hearted model. (J/k I don’t know enough about English monarchs to make this analogy work, so one of you nerds should give me the appropriate example.) The danger with this model of ruling is three-fold. First, you’d better stay personally popular! Mobs can turn—and turn quickly—against their instigators. Second, mobs are blunt instruments and unsuitable for 99.9% of all political tasks. (Admittedly, the threat of a mob can be potent if you can figure out how to use it.) Third, personal popularity is hard to transfer. Strong King with Failson heir apparent is a cliche for a reason.

Yesterday is a good crystallization of all this. The whole point of yesterday’s Trumpkin posturing in Congress was to pay symbolic fealty to the President; everyone knew Trump didn’t have the votes to stop the certification, so this was an opportunity for Trump’s vassals to come and kiss the ring. But in classic fashion, Trump himself was the last to know this was what was going on, so he stirred up an angry mob and the mob embarrassed themselves, the GOP, and the nation. It didn’t even effectively delay the certification: Trumpkins had planned to object to four or more states, and the rules meant that each objection would result in two hours of tedious speeches in the House. Between the speeches, voting, and the shuffling back and forth between chambers, they might not have wrapped up until 6 or 7 this morning. Instead, the mob action humiliated enough members of the Senate to pare back the objections and they wrapped up around 4:00 AM. Meanwhile, Trump’s actions seem to have burned some amount of his political capital and popularity, with scattered resignations and rumors of the 25th Amendment being invoked (hah!). Trump is successfully stoking a GOP civil war. I suspect (and predict!) he will win it, but it will be longer and bloodier than is necessary.

Vanquishing his foes in a bloody civil war will, undoubtedly, strengthen Trump’s despotic power in the GOP, but it will do nothing to improve his infrastructural power. For the foreseeable future, GOP operatives and politicians will have to kiss Trump’s ring and beg his favors. But will he effectively run the party? Laughable.

Two big take-aways:

1) There’s lots of Josh Hawley talk today, and all that residual anxiety about Trump 2024 or Don Jr. 2024 or whatever. Will the next one be a competent despot? In Mann’s schema, states with high despotic power and high infrastructural power are totalitarian states, so that would be a worrying development.

I am not that worried about it, however. Hawley isn’t Trump. Nor is Ted Cruz. I also correctly predicted Trump would steamroll through the GOP primary after the first GOP primary debate in 2015 precisely because none of those other guys match his magnetism or charisma. Whatever else you can say about Trump—and, lord knows, I’ve said a lot—he is uniquely and authentically Trump. It is not a performance or a bit. Hawley and Cruz are the lads from the Junior Achiever Club cosplaying Ben Tillman. If they prevail, it will be by reassembling some diminished version of a pre-Trump GOP political coalition. And whatever creature authentically emerges from the Trumpkin morass, my guess is that they too will be a diminished version of Trump, leading a diminished band of Qanon weirdoes. The more banal (if appalling) aspects of Trump—the racism, chauvinism, contempt for the vulnerable, etc—have been there all along and those currents cut across the electorate and parties to varying degrees. But the Qanon weirdoes will, henceforth, also be a more regular part of formal American politics, not as the outer-boundary of respectable politics, but as a faction that has to be constantly accommodated and managed. The result will not be a suspension of the constitution; but the ongoing winnowing of effective governance, the shrinking of our collective ability to do good.

In other words, there is no political apocalypse—for better or worse—just the continuing slow rot and fragmentation of an empire in decline. Trump is a perfect avatar for America’s imperial future, ironically manifest in our imperial present: all despot, no infrastructure. For the world, that may be a good thing, but I don’t want to undersell the violent possibilities of our imperial death throes. My sense is that we will, as we have always done, externalize that violence against people overseas and the “not American enough”s at home.

This is less a policy than a plea: the only ethical response is for Americans to renounce the desire for empire, internal and external. We must renounce it, for it was an evil prize all along and we have lost it all the same.

2) Trump has broken me, sundered me in two. I have long styled myself as a hard-bitten political realist, who would never do anything so foolish and ahistorical as to get caught up in the “politics of personality.” Politicians were avatars of larger, mostly material forces—primarily racial capitalism and settler colonialism in the US—but their personalities, predilections, and idiosyncrasies? I didn’t think it mattered. What mattered was the forces beneath that expressed themselves through political movements that were then narratived, through media, into moralized personages: the politicians. I was repelled by liberal vitriol at GW Bush—he was evil, stupid, corrupt—because it seemed to me to be a way of freeing us from our own culpability and relationship to the historical forces that produced him. Moreover, who really knew anything about Bush? I had never met the guy. I hated his policies and marched against the war. But so what? I was still a citizen of his empire, still responsible for the bombs incinerating Iraqis. It didn’t matter if Bush was stupid or brilliant, well-intentioned or malicious. The well-intentioned bombs killed just as well as the malicious ones. I never mustered hatred for Bush, no matter how fiercely and angrily disgusted I was with his policies, or at least hatred I could separate from my hatred of violence I for which I was also culpable. Similarly, I found the “audacity of hope” mostly insufferable and bearable only because my realist inclination told me it was effective political rhetoric. But I would never be so naive as to believe any of it! Right? Right?

As Peter Sloterdijk memorably argued, the misery of enlightenment is the stunning realization that knowledge is not always power. That, to the contrary, arming ourselves with a penetrating cynicism does not liberate us. Or, as Eve Sedgwick put it, it is sometimes the dreadful fate of the powerless to have to know and the privilege of the powerful to remain ignorant.

Today, I cannot retreat from my analyses of the deeper social forces at work in contemporary American politics. But I think I would have learned nothing—not a single damned thing—if I claimed that the personal idiosyncrasies and psychologies of Trump were not a potent historical factor that cannot be reduced to those deeper currents. I hate this. I hate it so much and I hate Trump for it. I want to believe that Trump is pure symptom. I would be a better Marxist, a better historian, if I could believe that. But I don’t believe it, at least not enough, and that ambivalence—bi-valence; “between two powers”; literally, torn in two directions—rips me apart.

Trump is my mirror. When I look at him, I see myself and I see, then, my self cleaved: the materialist I desire to be and the liberal I cannot escape.

ETA: I’ve copy-edited this from the original version, caught a few errors, and made a few minor stylistic alterations I thought preferable. The only substantive thing is that I weakened the parenthetical in the first paragraph, which overstated my certainty and the credible reporting that the feckless police response was “by design.”

Edit: "overseas" in place of "oversees" -- and a couple of instances of "it's" where it should say "its." Otherwise, really insightful piece, Gabe. Would love to see it published. Your use of Mann to explain the dynamics of different versions of state power is helpful. I couldn't help but recall James Scott's argument that all such efforts are fool's errands, that even when states have the despot and the infrastructure figured out, they still founder on the waves of local complexities they seek to control. Or at least they can, sometimes. Going forward, it will be interesting to see how the GOP navigates those complexities. Changing demographics are a big one, but of course there are others.

edit: cache when you want cachet…

I find myself in violent agreement with this. Thanks for bringing this into more clear focus.