Political Science, Authoritarianism, and Climate Change

Can the Climate Crisis Undermine Democratic Legitimacy?

Editor’s Note: As I mentioned in the preface to Ariel Ron’s post two weeks ago, I’m trying to use the limited amount of subscription funds this newsletter generates for something more productive than feathering my own nest. Namely, I’m using it to pay writers I admire to write the sorts of texts I admire. Along those lines, I’m thrilled to introduce today’s guest post from my brilliant friend, Jeremy Wallace. Jeremy is an associate professor of Government at Cornell University, studying authoritarianism and focusing on China, cities, statistics, and climate change, which he writes about on his substack: The China Lab (you should subscribe!). His forthcoming book, Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts: Information, Ideology, and Authoritarianism in China, argues that a few numbers came to define Chinese politics until they didn’t count what mattered and what they counted didn’t measure up. Relevant to the piece below, he also wrote (with Michael Neblo) “A Plague on Politics: The COVID Crisis, Expertise, and the Future of Legitimation.” On climate change, Columbia University’s Center for Global Energy Policy published Gatekeepers of the Transition: How China’s Provinces Are Adapting to National Decarbonization Pledges, a report he wrote with Ned Downie. Above and beyond his sterling academic credentials, many, many decades ago Jeremy also went to high school with me. And he bossed me like an expert authoritarian as the captain of the speech and debate team. Bossing me is no easy feat, so you can be certain that Jeremy knows what he’s talking about when it comes to today’s topic. Take it away, Jeremy!

A recent political science article claimed that if democracy fails to adequately respond to the climate crisis, then ‘political legitimacy may require adopting a more authoritarian approach.’ A furor ensued—eco-fascism, Fox News, and more—that muddied the waters instead of clarifying them. Academics need to do more to engage in the climate debate, and to do so thoughtfully, both in journals and in public. The nature of digital debate often makes that difficult, with more views accruing to wilder claims, but responsible scholarship requires slowing down the debate and resisting the lure of internet sensationalism. The climate crisis is a global phenomenon that is unfolding now and will continue to do so over the course of many human lifetimes. That scale makes it thornily resistant to simple narratives of cause and effect.

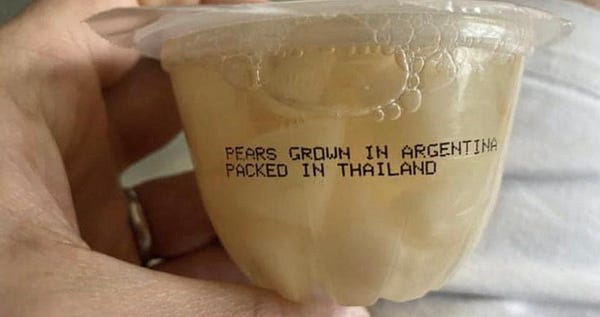

Consider the following tweet.

A trail of crumbs has been laid out with the implied chain of logic like a game of connect the dots, all the more compelling to the reader for having to finish the work. It feels natural to assume that taking a pear grown in Argentina, sending it to Thailand for packing in plastic, and subsequently sending it back across the Pacific Ocean to the United States to be eaten would involve production of significant amount of pollution—namely, emissions changing the atmosphere and warming the planet. Surely all of this distance would trump any kind of problem arising from natural, wholesome, local beef production. Think of all the labor and logistics involved, the machines, the vehicles, the time. The tweet preys on our frustrations with modern globalized capitalism, to mask self-interest and status quo bias, for of course the tweeter here is a dairy farmer who is not particularly interested in your pear consumption habits but is deeply wrapped up in continued bovine agricultural production.

Yet studies that have investigated the emissions associated with different kinds of agricultural production are quite clear. Transportation is almost always at under 5% of emissions of a given product. In the end, it is what is on our plates, not the elliptical journeys that it takes on its way there that matters. But despite its consistency in statistical analysis, this result clashes with our own lives. Transportation is a major source of carbon emissions for people living in the developed world; depending on the length of your commute and mode of transportation, it is quite likely the majority of your emissions. Extrapolating from the individual-level to the crazy complexity of globalized capitalism is difficult and non-intuitive. Large container vessels exist on a scale in size that is hard to fathom. A Suezmax container ship such as the Ever Given, which was you may remember was a main character from 2021—stuck nearly sideways for six days blocking the Suez Canal and the billions of dollars in goods that it transit daily—is 399.9 meters long. Its dwarfing of the excavator that tried to help push it back into the deeper channels of the canal makes plain the immensity of these craft. It can carry 20,124 standard twenty foot containers; that’s a lot of pears.

With most food being shipped via such efficient means, there is little in the way of emissions per mile. So unless one is eating a lobster flown in that evening from half a continent away, there is little to be concerned about in terms of transportation emissions in food. On the other hand, cows burp out copious amounts of methane in their digestive process, and methane is eighty times more potent than carbon dioxide in its climate forcing, although it does stay in the atmosphere for a shorter period of time.

So, the farmer’s tweet calling to cancel pears attempts to perpetuate the status quo by taking advantage of the complexities and attitudes of those who might see it, masking self-interest with conspiratorial language. Of course, it’s just a tweet. And, as such, exists at the heart of an ecosystem pushing vast quantities of information in front of our eyeballs, draining our energy or evading the intellectual defense of skepticism that might have triumphed if one pondered beyond the half a second that it shows up on your phone screen while you scroll down to see something, anything else.

Climate change’s complexity interacting with a technology that makes sharing information instantaneously so simple and considered deliberation so impossible in a context of democratic decline recently yielded what can best be described as a brouhaha for the discipline of political science. But it is precisely because of these forces remapping our world that demands that we try to have these conversations, to clarify different values and viewpoints, to assess tactics, strategies, and logistics, to consider likely failure points, and to imagine better futures. It will not be easy, but needs to be done, both with passion and clear-sightedness.

In December, the discipline’s leading peer-reviewed journal, the American Political Science Review, published an article entitled “Political Legitimacy, Authoritarianism, and Climate Change” by Ross Mittiga. The discipline as a whole, especially APSR and other top journals, has neither taken a great interest in nor published significant materials on climate change.

As someone who considers this topic vital, I was excited to see a new piece in the discipline’s top journal, and as one does these days, tweeted about it based on a quick perusal of the abstract. Almost immediately others alerted me to potential red flags, so I attempted to read the article with sufficient care and communicate with others about their reading of the pieces as well.

As is likely clear from its title, the article covers very charged material. It begins by invoking authoritarian success — “As the climate crisis deepens, one can find a cautious but growing chorus of praise for ‘authoritarian environmentalism’”—but quickly shifts to lingering on democratic failures in addressing climate change—“it is undeniable that nearly all wealthy democratic states have failed to respond adequately to the climate crisis.”

It uses this frame despite what I will call the Footnote Two Problem. In the piece, the second footnote highlights that existing research points in favor of democracies doing more than authoritarian states on climate change. This result exists even though many living in democracies remain frustrated by the inability of their governments to take action sufficient to be crisis. This feeling (a totally reasonable one to have that I share deeply!) does not translate into a comparative analysis of the efficacy of authoritarian states. The empirical scholarship that has been done suggests that democracies are comparatively active in acting on or mitigating climate change compared with non-democracies.

Let me quote the footnote in full:

According to Stevenson and Dryzek (2014), there is at least some evidence that more deliberatively democratic governments perform better. See also Looney 2016; Povitkina 2018; Shahar 2015.

The footnote in total mentions four pieces. Obviously the first, Stevenson and Dryzek (2014), supports the notion that democratic governments do more on climate change. So to do the second and third. In “Democracy Is the Answer to Climate Change,” Robert Looney’s stance is clear from the title. The same can be said from Dan Shahar’s: “Rejecting Eco-Authoritarianism, Again.” It is only the fourth study, Marina Povitkina’s, “The Limits of Democracy in Tackling Climate Change,” that perhaps suggests a counterpoint to this pro-democratic tide. However, even it comes to agree with the others, though it imposes one condition on that claim:

The results indicate that more democracy is only associated with lower CO2 emissions in low-corruption contexts. If corruption is high, democracies do not seem to do better than authoritarian regimes.

The Footnote Two Problem is this: the article’s frame takes democratic failures as destroying the legitimacy of those regimes, implying growing legitimacy for authoritarianism—but authoritarian failures are worse.

Yet this recognition of the existing data feels overwhelmed in the piece. On page two, the article says

To be clear, though, the argument presented here should not be understood as an endorsement of authoritarianism but rather as a warning: should we wish to avoid legitimating authoritarian politics, we must do all we can to prevent emergencies from arising that can only be solved with such means.

But why should we expect that the climate emergency “can only be solved with such [authoritarian] means” when just a page before footnote two presents the result from scholarship to date that democracies have done more than authoritarian states to avoid the worst outcomes of climate change?

The paper’s use of “authoritarian” is a bit incoherent. The literature in footnote two treats it as one regime type on a spectrum running from democracy to authoritarian (or splitting country-years into one or the other). This fits with most scholarly and colloquial uses of the term. But authoritarian is also used to describe particular actions or governance practices that deviate from some kind of liberal democratic ideal. Or, as Peter Cannavò noted, there is a conflation of democracy with liberalism.

“Authoritarian climate governance” ranges the gamut from on one end “curbing meat heavy diets,” installing “a censorship regime that prevents the proliferation of climate denialism or disinformation in public media,” or “imposing a climate litmus-test on those who seek public office, disqualifying anyone who has significant (relational or financial) ties to climate-harming industries or a history of climate denialism” to, on the other end, court orders consistent with due process like the “Netherland’s Supreme Court’s decision that Shell was in violation of Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.” Democratically-elected officials passing laws that subsidize clean power, tax fossil fuels, or require coal to be left in the ground is not authoritarianism even if it does represent a break with prior propertarianism.

One can imagine a different framing and language that does not rely on slicing regimes neatly into democratic or authoritarian categories but instead rests on ideas about delegation to technocrats with some (limited?) democratic backstops. After all, as Kate McNamara put it: “we have been debating EU ‘output legitimacy’ for decades & the legitimacy of technocratic delegation to independent central banks …”

One can read this in two different ways: the article rips the mask off of the tremendous power that “technocrats” have in existing institutional settings by calling them all authoritarian. Or, by muddying the waters between systems that empower elites but maintain some democratic checks and systems that do away with such checks leaving technocrats unencumbered by the demos, the argument readies the way for anti-democratic action to manage the climate crisis.

But, this was over the holidays, and reading and thinking takes time. Then on New Year’s Eve, a thread critiquing the piece went viral on twitter.

Let’s pause here for a modern moment of zen and ponder the locus of authority. Does it rest in the peer-review process in prestigious but generally inaccessible disciplinary journals or in a viral Twitter thread about said article that likely has 1000x the readership of the original piece?

The text of this first tweet already shows that a misreading has taken place. Mittiga explicitly argues that this argument is a warning, not as an endorsement. And yet, the article’s argumentation proceeds from the premise that authoritarian governance would be legitimated by democratic failures to address climate change challenges despite the empirical record of dictatorships doing even less than democracies to this point.

The article’s key move is to separate legitimacy into “foundational” and “contingent,” with the former focused on keeping citizens alive and the latter on how those lives might be lived. The question of whether there are circumstances where life should be sacrificed for freedom or freedom for the sake of preserving life is a classic one, but there’s little acknowledgement in the article about how security is always partial and tradeoffs between these values is inherent to human communities. Take speed limits. Despite fewer miles being driven in 2020 than in previous years, more Americans died in car crashes; the general assumption is that this is due to speed. Crashes at higher speeds are much more likely to be fatal. But speed limits are chosen to try to balance the dangers of moving half-ton steel cages with people inside with the desire to allow people to move about their environment. Debates about whether the status quo gets that balance right persist—see the Vision Zero movement—and even whether limiters should be installed to keep automobiles at legal velocities.

The argument can seem to be tilted in favor of authoritarianism as it barely weights the freedoms of democracy, leading to readings like this from the viral thread:

Note that Wuttke continues to quote the actual article and engage with its substance, if continuing to pull selectively from it, but also that the engagement numbers this far down the thread have dropped off markedly.

The quote tweet phenomenon allows or encourages amplified simplification (of an already simplified bit of discussion in the tweet / thread). Many drew connections to COVID-19 policies, suggesting that “They’re going to try to push climate lockdowns. Don’t let them.” Or even further: conservative blogger and radio host Erick Erickson said “This really is becoming a new religion with jihadist sensibilities.” Economist Noah Smith wrote “The kids call this ‘ecofascism’, I believe.” On the anniversary of the US capitol insurrection, Fox News published a story about the article saying that it “suggests 'authoritarianism' might be necessary to fight climate change.”

These critiques are unfair to the article and led to a circling the wagons by political theorists.

Who are we in conversation with? What grants legitimacy to “actual fascists?” A junior scholar writes an academic article that goes through peer review and is published. It knowingly engages in “unsettling” debates and through some combination of its own limitations, the non/misreading of others, and the amplification of Twitter, millions of impressions are made. Can we count on the fact that “Twitter’s memory is that of a goldfish” to dismiss this as a tempest in a teapot?1

The environmental movement, after all, has had dalliances with authoritarian practices, perhaps most troublingly when the topic turns to population. Garrett Hardin’s extremely influential idea of the tragedy of the commons was not just wrong empirically when Science published it in 1968, its subheadings—e.g. “Freedom To Breed Is Intolerable”—make transparent the authoritarian leanings of his lifeboat ethics. The Ehrlichs published The Population Bomb that same year, and the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth followed in 1972. The Chinese rocket scientist Song Jian leapt to attention and thrust himself into demography, stressing the ease with which one can switch “missile velocity, position, and thrust” to “population density, death rate, and migration rate.” His intervention was critical to the One Child Policy on the Chinese people, arguing that without it the country would likely fall into a Malthusian disaster. While post-hoc China has claimed that the policy helped protect the climate through reducing the number of people born, there’s serious debate whether economic growth is a better explanation for the decreased fertility rate. What we do know is that local officials zealously implementing the policy coerced women into abortions and sterilizations.

And this must be a major concern for those so frustrated with the piecemeal and pint-sized political responses of democracy that assume that the grass must be greener on the other side. Not that authoritarians will use their awesome powers to rapidly decarbonize and save the world, but that the pretext of ecological catastrophe will be used to justify their existing agenda. Nils Gilman refers to this as “the coming Avocado Politics”

Avocado Politics”: green on the outside but brown(shirt) at the core. The term is an ironic nod to a moniker used in the 1970s and ’80s to describe the green parties in Western Europe: “Watermelon Politics” — green on the outside, red on the inside….

Avocado Politics is the parallel phenomenon on the Right: just as watermelon politics repackaged the political wish list of the Left on the basis of the environmental crisis, Avocado Politics reiterates the policy agenda of the far right, but now justified on the basis of the environmental crisis. As traditional conservative parties crumble and the far right gains power in many countries, embracing the reality of global warming is likely to be used to provide a powerful new set of justifications for the far-right policy program.

In the recent China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet, Li and Shapiro distinguish between depictions of China that uses its authoritarianism to achieve environmental ends and what they see as more dominant: state-led environmentalism that has non-environmental spillover effects, most notably on the centralization of political power and the suppression of individual rights and public participation. “In the name of ecological wellbeing, the state exploits the environment as a new form of political capital, harnessing it in the pursuit of authoritarian resilience and durability.” Mittiga fails to grapple with these ideas about the justificatory power of environmental rhetoric pursuing other ends. Authoritarianism here is just an effective engine for environmental action if democracies continue to fail.

But beyond the explicit framing of the paper as a warning, Mittiga’s argumentation is not that we should ignore contingent legitimacy, but instead that

[Patrick] Henry is criticizing the idea of authoritarian power being used in normal (non-SOE [state of exception]) conditions to maintain an artificial peace. My argument, however, is that relaxing or suspending CL standards is justifiable only when—and to the extent that—doing so is necessary to address serious and credible threats to citizens’ safety.

But citizens’ safety is always partial, even in normal times. Nevertheless, continuing this line then moves us to a discussion of when we can know an emergency when we see one that allows for normal politics to be pushed aside, Schmitt’s state of exception. Climate change, it is argued, is an emergency in two ways: an emergency of effects, because of the daunting scale of dangers to human life, and an emergency of action, because “the time window for preventing these dreary outcomes is rapidly closing.” While the scale of the climate crisis merits consideration as an emergency, the ticking clock embedded in the “emergency of action” conception is wrongheaded in two ways. The damages are already here, and at the same time there is no cliff that we are about to walk over, no explosion about to wreck the whole world.

This latter misunderstanding is cinematic and pervasive. In Adam McKay’s satirical Don’t Look Up, a nine kilometer wide, ‘planet-killer’ comet is discovered to be on trajectory to slam into earth in six months. American elites in government, media, and business manage to fail to deflect the celestial body which (*spoiler*) obliterates all human life on earth. Written as an analogy to climate change, the movie has received serious plaudits from those banging the drums of the climate emergency as “the first good movie about climate change.” But while many aspects are enjoyable, its notable and telling failure to understand climate politics mirrors Mittiga’s article.

The comet as ticking clock fuels the movie’s momentum and drama, but it does not translate into the climate change space. Rather than a step-change from a comfortable world to a too-hot and dangerous one, continued accumulation of climate forcing gases in the atmosphere is shifting us along a distribution of probabilities, making formerly rare occurrences more common and difficult to conceive of events like the heat island over the Pacific Northwest last summer that killed hundreds of people and billions of animals possible. Weather is always variable and random day-to-day, but now the game is being played with loaded dice that are become more so over time. If we pass the 1.5 or 2 degree lines that the COP negotiations highlight, those indicate greater damages and increased likelihoods of passing thresholds but ultimately they are arbitrary lines in the sand that we are drawing based on the metric system. David Wallace-Wells of The Uninhabitable Earth fame recently wrote that the worst-case scenarios are looking less and less likely.

If there are tipping points where positive feedback will make it difficult-to-impossible to return to where we are now, these are not yet known. For some places, we’re already there (low-lying islands, king tides flooding coastal cities like Miami and Boston, fire-prone California communities…). A meta-study of such the economics of such tipping points suggests that they should factor into our assessments of the costs of climate change, but one of the authors, Gernot Wagner, wrote about the study that “There are good reasons to believe that extreme weather events like floods, droughts, or hurricanes may have much larger economic impacts than the kinds of large-scale planetary ‘tipping points’ we focus on.”

More significantly, air dirty from smoke from burning things, mostly fossil fuels but also wood, crops, and forests, is killing millions of people now. Not in the future. Now. This is already happening. Death on that scale is hard to process, but few if any climate-emergency-amplified crises seem likely to kill as many as quickly.2 The emergency is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed and in a form different than most of us think.

The probabilistic nature of climate change impacts also affects the way people consider them. People tend to ignore differences between very low probabilities. People aren’t going to cavalierly give up eating meat or driving just because experts believe that there is a better world if these things were to happen. Technocratic limits are compounded by the collective action problem — what’s one extra hamburger in all this madness? Why should I give it up if nobody else is going to?

Don’t Look Up falls into what I think of as The Daily Show trap of lamenting failure in a way that generates catharsis but without creating any intention or action. Its depiction of a morning news show, The Daily Rip, is a place that ignores the significance of things and simply laughs at reality. Its hosts at the moment of impact are more explicit—they just want to talk shit about people—which could serve as an encapsulation of Don’t Look Up’s critiques.

Indeed, basically all American elites are targets in the film. Only science is held out as worthy of praise — yes, he takes a swipe or two at Leonardo DiCaprio’s astronomer as an individual and sees institutionalized organizations (NASA) as corrupt — but the totemic chants of “just look up” and “trust the science” suggest a desire for scientific daddies to come take over and solve the world’s problems. Peer review has never been as significant a plot point in a Hollywood picture.

But peer review just means that a couple of scientists have dutifully agreed to an act of unpaid service to the broader disciplines and assess the quality of another piece of scholarship. And so we return to the Mittiga paper and the disciplinary brouhaha.

Like the movie, the paper does not deeply consider the global nature of the climate crisis. Should Belgians give up democracy in order to achieve a tiny bit more mitigation when their total share of global emissions is less than 0.27%? When Hebei produces more carbon dioxide than Germany, these details matter. Even the United States was only 14% of emissions in 2019. China’s centrality to global emissions today and tomorrow is difficult to overstate, and of course, it’s already authoritarian.

In some ways, Mittiga is trying to have his cake and eat it too regarding authoritarianism. While the paper starts out saying it’s just a warning, by the end it comes closer to an endorsement. Here’s the final sentence:

“if adhering to CL (contingent legitimacy) factors proves incompatible with responding effectively to the climate crisis, then political legitimacy may require adopting a more authoritarian approach.”

That’s going further than a warning that a failure to act may lead to authoritarianism; it says political legitimacy may require authoritarianism. This is a strange place to end up, not just because of the weak empirical basis for preferring authoritarianism on climate change grounds (the Footnote Two problem) but that legitimacy itself has become the reason to adopt authoritarianism. This gets things backwards. We care about values, actions, and outcomes. These are the where legitimacy comes from; a government that prioritizes its own legitimacy above other factors is a dangerous place to be a citizen.3

Science, especially social science, isn’t perfect. Flawed pieces, flawed readings, flawed institutions, flawed people, flaws all the ways down. The goal is just to improve on the flawed work that is out there already. These flaws are why the religious tinge of “I believe in science” has always rankled me. As the changing understandings of COVID-19 make clear, science is not inherently true but it is self-correcting. Scientific understandings are only part of a conversation. They can clarify what risks are out there, give estimates of the effectiveness of different interventions, predict the probability of different outcomes, and more. But science has no way of assessing the warm feelings you get from making homemade pork dumplings with your family for lunar new year against the carbon emissions from industrial pig farming. Thinking through tradeoffs like these is not a matter of calculation but of human conversation.

We need to try to have more of these kinds of conversations. Or rather, we need to acknowledge that these conversations are happening already and either participate in them or not. I’m of the opinion that my colleagues in political science are smart, thoughtful, and well-trained in thinking through issues of political economy in systematic ways. Having more of us in these conversations will help rather than hurt the discourse and policy discussions that arise from it.

The footnote two problem is an empirical one for this article, but it would be important to know if the existing research pointed in the other direction — that authoritarian regimes were better at climate mitigation — not that it would justify some kind of Gaia dictatorship but to treat the world, its citizens seriously and honestly rather than rejecting certain types of results because they are morally objectionable. APSR should attempt to have as limited of an editorial line as it can (rather than print only defenses of democracy given that democracy is ostensibly in decline). Who’s democracy? Helene Landemore’s Open Democracy? Dahl’s Polyarchy?

As Erin Pineda pointed out, studies in our discipline often have morally chilling possibilities inside of them, such as a well-cited paper which found indiscriminate state violence to be less likely to provoke insurgent response than more precisely targeted violence. My first book, Cities and Stability: Urbanization, Redistribution, and Regime Survival in China, examined China’s “management of urbanization,” which helped account for the country’s economic development and political stability. The foundation of that management was (and is) the household registration system, which discriminates against those who happen to be born in the Chinese countryside. One could try to claim that the book justifies this system or recommends it for other countries trying to develop their own economies. On page 33, I try to head off this interpretation with the following text:

There is, of course, an ethical component to what amounts to an effective restriction on the basic freedom to locate here. I offer explanations but not justifications for the policies of migration restrictions that dictators put in place. I simply attempt to improve understanding and bring light to previously murky areas of political behavior in nondemocratic contexts.

Perhaps you think this is insufficient, that more space should have been devoted to my ethical qualms with the system and the inequality that it engendered. That’s fine, but I do insist that developing better understandings of and explanations for how our societies work is part and parcel to the conversations about how to change them for the better.

And on climate change, these conversations are definitely already happening. Andreas Malm published How to Blow Up a Pipeline in the past year. It’s already been a couple of years since Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright published Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future. The economist Gernot Wagner just published Geoengineering: The Gamble.

Debates about where the infrastructure to power a clean energy transition should be built are happening in town councils, state legislatures, and yes, on twitter every day. NIMBYism is always a difficult foe, and there are hard political questions here. How should the lithium that powers the modern battery revolution be mined, and how should its global benefits be weighed against local costs on the places where its extracted? Cobalt? Were Maine voters right vote down a gift to their (hated) local utility or are they responsible for the New England grid running on oil this winter when they blocked power lines to bring in hydropower from Quebec? How can a chapter of an organization literally called Sunrise support a solar moratorium? Well, does the solar facility really need to chop down an old-growth forest? The New Yorker just ran a fascinating profile of “eco-protestors” who chained themselves to trees and then lived in tunnels attempting to block … high-speed rail. American environmental groups have strong anti-development impulses from their conservationist origins that served them—and the environment—well for decades. But decarbonization requires clean electrification, with massive investments in new infrastructure, and those impulses can be hard to shake.

“Authoritarianism” is often appealing as a way to slice through the indecisiveness of deliberative governance—it’s sometimes pitched as “the end of politics”—but authoritarian states still have politics. Beyond that, the scale and fractured nature of the climate crisis guarantees there will be no decisive end, no point when we can be certain of a path out of crisis with minimal tradeoffs. No governing system—authoritarian or democratic—can offer that, and it remains the difficult task of political scientists to refuse the fantasy of that kind of resolution.

The climate crisis will be a dominant feature of 21st century life on Earth, political scientists need to be able to debate these issues and take them seriously, in our journals and throughout the public sphere with all of its context collapse and gamification. And we need to treat it rigorously, thinking systematically about the complex interplay of psychology, sociology, economics, and politics.

Apparently this saying, like many descriptions intended to separate humans from our animal brethren, is unfair to goldfish, which can make memories lasting weeks or even months.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future begins with a heat wave in India that kills 20 million, which if you took the heat dome from the Pacific Northwest and planted it in just the right location at just the right time and extended it for another full week could plausibly happen.

“This suggests that FL (foundational legitimacy) is also intimately related to trust or confidence in a government’s long-term capacities and ability to endure. Even if a state is characterized by peace and material sufficiency in the present, should it be sufficiently vulnerable to future threats—such that at any point it could plausibly no longer be able to respond to an emergency, maintain order, and protect citizens—then it appears that government already lacks FL.” p. 4. The problematic nature of a self-interested government prioritizing its own future above the lives of citizens is tossed off as not a problem for the argument in an example about police violence against protestors in Chile that is supposed to be seen as obviously objectionable, but the point remains deeply concerning.